France

First Round of Presidential Elections: Macron and Le Pen in the Run-off and Defeat of Traditional Parties

Der französische Präsident und Kandidat der Partei La Republique en Marche (LREM) Emmanuel Macron, spricht zu Sympathisanten nach den ersten Ergebnissen der ersten Runde der französischen Präsidentschaftswahlen am 10. April 2022

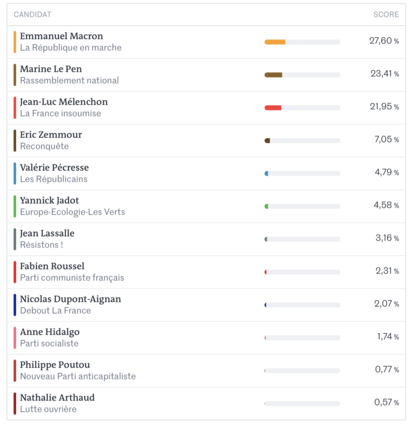

© picture alliance / abaca | Blondet Eliot/ABACAIn the first round of the French presidential election, the incumbent French President Emmanuel Macron (27.6%) and his rival Marine Le Pen (23,4%) from the far-right Rassemblement National have qualified, as expected, for the run-off on 24 April. This means a repetition of the run-off constellation of the last presidential election in 2017, albeit under completely different circumstances. Until late at night, there were rumours about whether third-placed Jean-Luc Mélenchon of the far-left party La France Insoumise could overtake Marine Le Pen; his result was eventually revised up from 21.7 to 22.2 and then back down to 21.9 %. While the gap between Emmanuel Macron and Marine Le Pen was only 2.7% in 2017, it has increased to 4.6% five years later.

All three candidates have improved their approval ratings compared to 2017: Emmanuel Macron by 3.6% (24% 2017), Marine Le Pen by 2.1% (21.3% 2017) and Jean-Luc Mélenchon by 2.3% (19.6% 2017). It remained unclear to what extent the so-called vote utile would play in, which describes a strategic voting behaviour consisting of voting for a candidate who has the best chances of winning the election, even if the vote does not reflect one's own convictions. In view of the weakened left Parti Socialiste as well as the Greens Europe Écologie-Les Verts, this phenomenon has taken full effect. Thus, Macron has been able to profit from the votes of the conservative Républicains and the far-left Mélenchon has been able to profit from the weakness of the Socialists. Many young people between 18 and 35 as well as non-voters voted for Mélenchon, as first projections by the Elabe Institute show. But the neck-and-neck race between him and Marine Le Pen was finally averted by the candidacy of the anti-capitalist Fabien Roussel (2.3 %). Without Roussel, a run-off between Mélenchon and Macron would have been far more likely, according to Brice Teinturier, director of the leading polling institute Ipsos, on France 2. Marine Le Pen, on the other hand, was able to score points above all in the middle age group, while Macron's electorate of 65 and over was particularly mobilised.

The clear losers were the traditional parties Parti Socialiste, whose candidate Anne Hidalgo dragged the party into complete irrelevance with a score of 1.7%, and Valérie Pécresse of the conservative Républicains. Pécresse missed the 5% hurdle with her score of 4.8%, which is important for the reimbursement of election campaign costs. Moreover, she was well below her far-right rival Éric Zemmour who was able to gather a total of 7% of the vote. The latter was thus clearly below the earlier opinion polls, which were still in double figures a few weeks ago, which is certainly connected to his lapses, among other things, towards Ukrainian refugees and Muslims.

Overview of the Results of the First Round of Elections

Decision Time Comes After the Elections: Appeals for the Run-off on April 24

Only a few minutes after the results were announced at 8pm, the defeated candidates took an immediate stand for the second round of voting. Several candidates appealed to their electorate to stand united against Marine Le Pen's far-right Rassemblement National and to vote for Emmanuel Macron on 24 April, including Green candidate Yannick Jadot, who at the same time called for private donations, as he also fell short of the 5% hurdle, the Socialist candidate Anne Hidalgo, the Conservative candidate Valérie Pécresse and the Communist candidate Fabien Roussel. It is questionable whether this reservoir of voters will be sufficient for the incumbent president, as only part of the electorate of the losing candidates will follow their advice. Particularly within the Républicains, it is far from clear how many voters will eventually vote for Macron or go one step further to the right. For instance, the former candidate for the race for the top position in the course of the party's primaries, Éric Ciotti, openly declared his sympathy for Éric Zemmour, but not for Emmanuel Macron. A part of the conservative electorate could therefore vote for Marine Le Pen. Even more problematic for Macron is the remaining electorate of far-left Jean-Luc Mélenchon, who called for an election boycott against Le Pen but did not encourage them to vote for Emmanuel Macron. Despite the phenomenon of gaucho-lépenistes, i.e. the migration of voters from the outside left to the outside right, this could also primarily result in abstention from voting. On the other side of the political spectrum, Éric Zemmour and Nicolas Dupont-Aignan called on their electorate to vote for Marine Le Pen on 24 April.

The defeated candidates, who pledged their support for Macron in the second round, were not sparing in their criticism of the incumbent president, stressing that a good half of all French people voted for an extremist party. Green candidate Yannick Jadot was particularly harsh on the incumbent, stressing that the call to vote for Macron was not a ‘carte blanche’ for the president. It is because of him that the extreme right has been able to achieve unprecedented levels of approval, as Emmanuel Macron has failed to ensure social peace, to involve the working classes and to take sufficient account of the concerns and needs of ordinary people. He should therefore "descend from Olympus", said Green MEP Karima Delli on France 2.

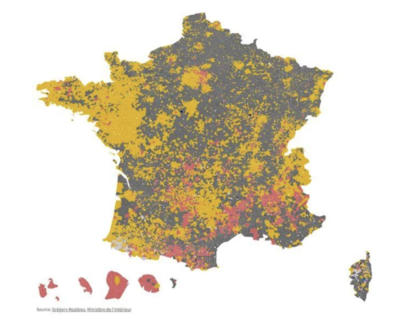

Geographical Distribution of Votes by Département

Very revealing is also a look at the geographical distribution of the electorate. Marine Le Pen was expected to perform particularly well in rural areas as she has always presented herself as close to the people and motherly in her election campaign. By contrast, Emmanuel Macron's movement lacks territorial anchorage as shown by the outcome of the municipal and regional elections. Yet, the incumbent president was able to score quite well in rural France, as can be seen in the figure, although his lead over Le Pen is particularly clear in large cities such as Paris or Lyon (in contrast to Marseille, which voted by a majority for Jean-Luc Mélenchon). On the other hand, Macron clearly lost to his far-left and far-right opponents in the overseas territories: Mayotte, for example, went out with over 40% of the vote for Marine Le Pen, whose fight against irregular migration is well received on the island state. Similar other overseas territories with few exceptions fell to Mélenchon or Le Pen. The radical left candidate prevailed in most of the overseas territories, in Ariège as well as in five departments of Île-de-France.

Abstention Record of 2002 Not Surpassed

At 26.2 %, abstention was not quite as dramatic as assumed in the last polls. Although abstention was almost 4 percentage points higher than in the last presidential election in 2017, it did not exceed the record level of 28.4% in 2002. The nevertheless high level of abstention could be mainly due to the feeling of many French people that the two candidates for the run-off were already determined long before the first round of the presidential election and that their vote would thus make little difference.

The increasing abstention could question the political support of Emmanuel Macron if he gets re-elected. Mobilising non-voters is therefore a top priority for him. He already announced numerous campaign trips in the north and east of France. As expected, he did poorly in these areas, which are heavily affected by deindustrialisation, and is now trying to convince the electorate that his economic reform course will not lead to further aggravation of the socially deprived. In his speech right after the results, Emmanuel Macron called on his supporters to unite in a "great political movement of unity and action for our country." without specifying what he meant by this exactly. Those close to him said that he had in mind a kind of umbrella party similar to the former conservative UMP, which would place different political sensibilities under a common house without the obligation to completely give up their independence. The question of party-political reorganisation will be decisive, especially with a view to new coalition arrangements for the parliamentary elections in June. It remains to be seen how sustainably Emmanuel Macron will succeed in turning his "fan club" of the La République En Marche movement into a new, larger party, now that the traditional popular parties are effectively in the process of dissolution. It is clear that Emmanuel Macron will have to convince a significant part of French society. His political opponents on the right and on the left will continue to dominate the political playing field, such as Éric Zemmour, who announced that he will not give up the "fight" to "take back" France. And despite their fundamentally different views of mankind, Marine Le Pen as well as Jean-Luc Mélenchon also advocate more sovereignty for the French nation and undermine cornerstones of international and especially European politics. Thus, the results of the French presidential elections should be studied with the utmost attention for the further shaping of a more competitive and resilient European Union with an enhanced capacity to act.

Jeanette Süß is European Affairs Manager in the European Dialogue Programme at the Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom in Brussels and coordinates the French activities there.