#FemaleForwardInternational

Not in Men’s Shadow Any Longer: The Rise of Female Leadership in East and Southeast Europe

Writing about women in politics in Southern and Eastern Europe is no easy task. First of all, one immediately invites anti-liberal anger that the topic is even raised. Secondly, it might also anger people on the liberal spectrum for trying to put too many, too different eggs in one basket. The greatest difficulty, however, comes from the complicated narratives within any single country in the region, and from the region as a whole.

On one hand, there are clear examples of anti-feminist backlash like the conservative wave that has swept over Poland and the ridiculous backlash against the Istanbul Convention in Croatia and Bulgaria.

On the other hand, we see countries like Estonia electing both a female President and a female Prime Minister and the top three EU countries where women dominate the science professions are Eastern European (Lithuania, Bulgaria, and Latvia). In addition, the examples of Polish and Turkish women’s resistance, including street protests, against the conservative authorities in their countries have resonated across the world and have shown that women in the region are far from helpless.

Economic empowerment vs. political underrepresentation

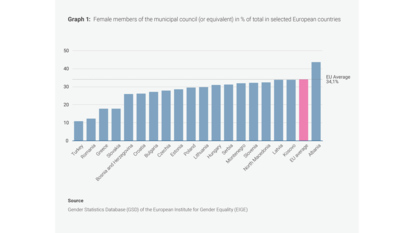

Seeing both sides of the coin makes casting judgment much harder. But there are some clear trends that cannot be ignored. When it comes to the general representation of women at the national level of politics, the worst-scoring countries are from the region (see Graph 1).

It is true that, overall, the EU still hasn’t reached an overall gender balance, even in the European Parliament, which is supposed to be a trendsetter though it can still only claim a 1:2 ratio between the two genders. But the difference is once again exacerbated precisely by the Eastern and Southeastern members, with the Bulgarian, Estonian, Cypriot, Lithuanian, and Hungarian delegations having less than 20 percent women, while the overall percentage of women in the institution is 36.

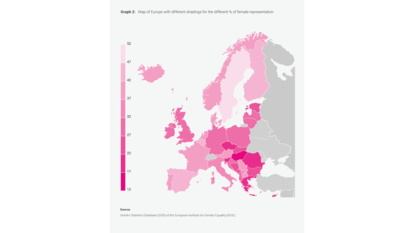

The situation is even worse when it comes to representation in regional legislatures, where Romania, Cyprus, Greece, and Croatia “boast” even lower overall levels of representation (see Graph 2). Only 19 percent of members of national governments, 6 percent of leaders of major political parties, and around 10 percent of members of regional assemblies and regional governments in the EU partner states are female, compared to about double that number in the EU.

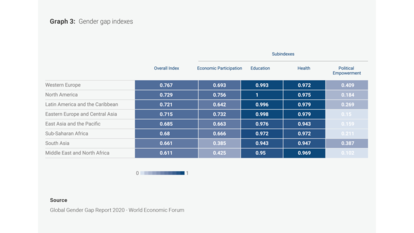

According to the 2020 Global Gender Gap Report of the World Economic Forum, the region of Eastern Europe and Central Asia’s high scores for Health and Survival and Educational Attainment is a top performer in the West and it even leads in Economic Participation and Opportunity. But on the level of Political Empowerment, the results are staggering – the region’s score is almost three times lower than Western Europe’s and, as a result, is lower than any other region’s except the Middle East and North Africa.

It is not only about formal representation in legislature. In fact, participation in politics or the lack thereof is a by-product of a wide range of problematic trends in the societies of East and Southeast Europe. One such issue is societal attitudes towards the role of women, and a 2019 poll by the Pew Research Agency on the topic of gender equality in different European states illustrates that well.

The study found that, whereas in Western European societies nine out of ten persons said that having equal rights regardless of their gender is important to them, in Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Poland, and Slovakia only seven-in-ten said so. In Russia, Ukraine, and, notably, Lithuania, this proportion goes down to close to under six out of ten.

Cultural attitudes, different economic opportunities, recent conservative trends, and a legacy of authoritarianism could be cited as other important reasons for these perceptions, though the list could go on and on. Let us examine them one by one.

The heavy legacy of culture

While culture has always been an easy – and often wrong – explanation for why some societies adapt to novel customs while others find it hard to do so, almost all female politicians FNF interviewed for the #FemaleForwardInternational campaign confirmed that in this region, societal norms have really affected them. At one point or another in their political careers, these politicians have faced some sort of backlash for daring to enter the political realm as women.

“I think in Romania being a woman is subject to many clichés,” says Diana Muresan, regional coordinator for the centrist Save Romania Union in the city of Sibiu and a recently elected municipal councillor. “You are expected to neglect your career and your dreams in order to maintain a household and raise children. It is expected for the husband to have a political career, to earn the money in the household.” Another young liberal, Monika Zajkova, a Member of Parliament from the North Macedonian Liberal Democratic Party, shares a similar concern: “We live in a patriarchal society, with a stereotype that women need to be housewives and that politics is none of their business; a lot of people say we are unable to make important decisions.”

Notoriously, even when many women do join political parties, they do it in order to fit within the framework “allocated” to them by the male majority rather than to carve a path of their own. An anecdote told by Croatian politician Diana Topcic-Rosenberg, who was previously part of the leadership of the GLAS alliance, illustrates this attitude pretty well. After a long and versatile career in international NGOs, on her return to her homeland she decided to see which political party she should join. “There were women's associations in the parties and when I got curious about what they were doing, I realized they were baking cakes for political events and were engaged in charity. I started wondering what they talked about when they baked cakes, do they talk about what they dream of for their daughters, what they want to change today so that they can live better tomorrow? No, they were exchanging recipes,” she recalls, half-amused and half-baffled. She adds that sometimes female politicians themselves are happy with the position allocated to them by the party heads and choose to follow party lines rather than raising their voices on topics that are important to women.

Popular distaste of politics

And those are only the cultural stereotypes that target women in politics directly. For many of our interviewees, other social norms are just as problematic for women who decide to try a public affairs career – albeit indirectly.

For most Western Balkan countries, one such shared social norm is the essential topic that dominates political discourse as a whole – anti-fascism. “There are still discussions in Croatia about who won the Second World War, but we don't want any of that, we know who won. Our country's constitution is established on the grounds of anti-fascism – so let's not talk about the war anymore,” says Marijana Puljak, who co-chairs Croatia’s newest party – the liberal Center (“Centar”) party and entered Parliament on its ticket in 2020. By talking only about the distant past, politicians from the mainstream left and right parties mostly just distract attention from much more pertinent issues: for example, human, economic, and social rights, and the anti-corruption effort. “We cherish the idea of anti-fascism, but we are talking about looking to the future and closing the gaps that divide our society, how to change the constitution so that all people have the right to be elected,” says Nasiha Pozder, a member of the Federal parliament of Bosnia and Herzegovina from the liberal party Nasha Stranka.

Then comes the pressure from the family, which is much more of a driving force in all the region’s countries compared to the West. Diana Muresan has felt that pressure twice – first, over the question of why she joined politics in general, and second – over why she, as a woman, is more proactive than her husband. “In the beginning my family didn't really understand our involvement. Because politics in Romania is not considered something you want to do, that good people don’t get involved in politics – this is the perception here. Our parents and relatives always told us – ok, you are successful people, you have your own business, you have travelled a lot around the world – why do you want to do that?”

Burden of an authoritarian past

Last, but not least, when it comes to cultural influences one cannot ignore the mixed legacy these countries’ recent authoritarian past had on women’s political participation. On the one hand, it is undeniable that Socialist regimes drastically improved female education and employment levels in the post-war years. The grassroots participation and the behind-the-scenes, inspiring influence of socialist women within this system of tightly controlled politics have been revealed in archival studies on Bulgaria and Yugoslavia, as demonstrated by US cultural anthropologist Kristen Ghodsee and Italian historian Chiara Bonfiglioli, respectively. At least on an everyday level, women’s equality was ensured, as testified by Diana Topcic-Rosenberg, who experienced the last years of socialism in Yugoslavia. “Croatia was part of the former Yugoslavia, a socialist country, and as a young woman growing up there, I didn't feel much of a gender gap in terms of opportunity.”

These examples, however, were the exception rather than the rule in the authoritarian socialist states that were gradually turning to nationalism in the stagnant 1970s and 1980s, with women pushed back into the “mother of the nation” stereotype of a darker past. “Socialism as ideology wanted to make men and women equal, but that was not the fact in Romania. If we speak about birth control, after a decree in 1966, Romanians were supposed to give birth to many children; as a woman, it was difficult to do something else outside of the family,” says Diana Muresan. She also underlines the lack of role models of Socialist-era women politicians – all big shots in government at the time were men. To Marijana Puljak, besides the ideological scars, another legacy of State Socialism that influences women’s choices today is the feeling that having a job is a “scarce good” that might be lost – so it’s better to not take chances. “I don't think it's something good most of the time, especially if you are not happy and you are told to stay safe, not to take risks. Safety is somehow overrated in the ex-socialist countries,” she says.

Neo-conservatism on the rise

This is just one of the lingering legacies of a “good old past” which is haunting East and Southeast Europe nowadays. Another potent danger for female representation – and rights – is the normalization of a special kind of neo-conservative discourse across the region. Fuelled by disillusionment with the way that the transition from authoritarianism into liberal democracy and market economy proceeded, societies east of the Oder River have one by one started spawning illiberal populist movements. “A fear of diversity and a fear of change, inflamed by the utopian project of remaking whole societies along western lines, are thus important contributors to eastern and central European populism,” Ivan Krastev and Stephan Holmes wrote in “The Light That Failed,” their illuminating study of the rise of nativism in the region. Promoting and protecting women’s political and other basic rights suddenly became another thing to be feared, rather than celebrated, by the powerful of the day.

“We now live in a time of change in all countries, and people are not always reacting in a good way when change comes their way,” says Diana Muresan. She thinks that, when change comes about, many people tend to look back into the past and start imagining it as a place where everything had been simple, perfect, and beautiful. Her colleague from North Macedonia, Monika Zajkova, shares this view and says that she sees in it the clash of generations.” “Maybe it is attractive to people that are still living with the image of a past when we had huge families, but now individualism is much more important than collectivism,” she says.

Sadly, many of the liberal female leaders relate that their colleagues from conservative and even socialist parties are often content with being “party soldiers” that follow, rather than stand up to, the often socially conservative lines of their factions. Diana Topcic-Rosenberg shared a case in which her attempt to push a cross-party bill on the protection of child privacy backfired because conservative Croatian female politicians refused to stand behind a “liberal” policy. “I called women from various political backgrounds to back it up. The law was about children, it had nothing to do with one being a liberal, a conservative, or a socialist, it had to do with the particular rights of children. But the women from the ruling party were against it simply because it was proposed by the opposition.” Her experience is an echo of what Nasiha Pozder has gone through in the Parliament of Bosnia and Herzegovina: “I have a hard time talking to female colleagues from the right-wing parties, but that is their position in the party talking. When they get a task from the party, you don't hear their female voice, you hear the party’s voice.”

There is a perception that women are more participatory, that they are oriented towards cooperation, that they listen more... I think a lot of this is actually stereotype.

Liberals still not living up to their own goals

An additional challenge is the fact that even liberal parties, supposedly on the forefront of progressive policies, lag behind in terms of female representation. According to the 2020 Women in Political Parties Index, part of the Gender Equality Report of the Liberal International, 56 percent of the liberal parties that are part of the International have never appointed a female leader, and most had neither leadership quotas (83 percent) nor a female wing (83 percent). “While the results in this report show that liberals are performing above average on female political participation, we still have much to do,” wrote the organization’s president Hakima el Haité in the preface of the report. “Many of our parties have still never elected a female leader. Some work remains to ensure that our party structures are equipped to record and follow up on the threats and harassment we know that female candidates and politicians face,” she adds.

Female politicians themselves sense the difference in social attitudes towards them. According to the 2021 study “Igniting her ambition: Breaking the barriers to women’s representation in Europe” issued by the ALDE Party, liberal female leaders feel that gender stereotyping is still prevalent and plays a big role in the party and national politics of their country. According to a survey of female members of the party’s European affiliates, 78 percent of the respondents from Eastern European liberal parties said that they disagree – somewhat or strongly – with the statement that men and women are valued equally in their country. None agreed strongly. While female leaders from Nordic and Western countries were also divided about the perception of men and women in their countries, the differences are huge – 49 percent of leaders from the Nordics and 60 percent in the West shared a similar view with their Eastern peers.

Ad hominem toxicity

Apart from those overarching trends that have negatively impacted the participation of females in politics, every single woman-politician FNF interviewed shared at least one story of the daily harassment she had experienced. From sexist remarks to media and male colleagues solely focusing on their looks rather than their policy, these underlining attitudes create a toxic environment that certainly dissuades many from participating actively in public life. “I was fighting for this important piece of land in the city of Sarajevo back when I was an activist, and I was called “teethy” by my opponents. It was not important what I was talking about, it was about mocking how I look,” says Nasiha Pozder, recalling her first experience of this sort.

Georgian lawyer and ex-Defence Minister Tinatin Khidasheli, who has over 30 years of public affairs experience under her belt, has a plethora of similar stories that illustrate the struggles of female politicians. “When I became Minister of Defence, the very first orchestrated and systematic attack against me was that I'd bring gays into the army,” she says. She also recalls moments when she was simultaneously “accused” of being Jewish, an agent of the Jewish-Hungarian financier and philanthropist George Soros, a Jehovah’s witness, and a Satanist (“because I am for gay marriage,” she notes) who wants to spoil Georgian children. “When I was Minister of Defence the only comments I heard were about the size of my earrings and what kind of lipstick I was wearing. It was funny, but for me it was not an issue – I didn't become Defence Minister out of high school or because my father promoted me. But psychologically it damages you and you ask – don't you have anything to say about the policies I am implementing, the budget money I am spending, about the projects I am running?” she asks rhetorically. She adds that never in her life she has heard anyone speak in a similar fashion about male politicians.

“It has happened to me, without affecting me as much as it might have hurt other women. But I know how it hurts, I've seen it with people, and it will not stop by itself. We need to take an active stance against that. We've seen it in the plenary of the EP, it is not as if it is happening only in deep rural Moldova,” says Ramona Strugariu, Romanian MEP from the PLUS/Renew Europe group. What keeps her – and other interviewees – going is their sense of responsibility and an ultimate belief in their own capabilities.

These examples might seem anecdotal to some, but now there is data to prove that they are the norm. According to the “Igniting her ambition: Breaking the barriers to women’s representation in Europe” report, a majority of liberal female leaders reveal that they have encountered sexism and harassment at some point of their careers. While over 32 percent say this happened only once or a few times, less than one-third say that they were never an object of harassment at work.

What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger

But facing resistance have not stopped FNF’s #FemaleForward ambassadors from taking up politics. What motivated them to do so, and why did they opt to join a liberal party – which is far from a popular choice in the region at this moment? For most, it was a natural choice – either because they felt that these are the only parties that share their values, or because they were disillusioned by the track record of the classical anti-communist right/post-communist left parties that have all seemed to have lost credibility during the decades of transition away from State Socialism. “Knowing the past of my country and knowing that my parents lived under an authoritarian regime with very few liberties made me appreciate freedom even more,” shares Diana Muresan and adds: “I identify myself with the liberal values and freedom is the value I cherish the most.” Her Georgian colleague Tinatin Khidasheli has an even more profound explanation of her choice of political ideology. “I am not simply a conscious liberal,” she says. “I am an instinctive liberal – it is not just from books, it happened to me naturally. When I was that age that determines your long-term choices, I was on the streets fighting communists. This fight for freedom defined the whole structure of my life forever.”

For all the women in the #FemaleForwardInternational campaign, it seems like the details of liberal ideology and the diverging schools of thought within it are of secondary importance in the context of their own countries. “What does it mean to be liberal here? It is not about details in your political theory – it’s more about answering questions. What is your opinion on gay marriage? Are you for adoption of children by gay couples? What about religious minorities – do you believe that all religions should have the right to practice the same way as the monopolistic Orthodox Church does?” Tinatin Khidasheli says. “So it is not about what kind of educational policies I defend or what sort of health or social care I want, no – it is still about the big issues we are discussing, the basics of freedom – mainly equality and equal access to life’s basics,” she adds.

On the nature of leadership

The fundamental reason for this divergence of opinions comes from the different understanding that female politicians have on whether leadership “has” gender. Turkish politician and businesswoman Zeynep Dereli is on the one side of the debate: “Women’s political participation has profound positive and democratic impacts on communities, legislatures, political parties, and citizen’s lives, and helps democracy deliver.” Others, like Tinatin Khidasheli, do not think there is anything special about female leadership that differentiates it from the male version. “I don't believe that strong, qualified, conscious leadership depends on gender. I think it comes from the honesty and professionalism of the person,” she says, and adds: “I know it is important [to encourage women to join politics], I do it every day, but at the same time I don't believe that we should get in this position and have this attitude that just because we are women, we can do a job better if we are given the opportunity. It's not like that.”

Diana Topcic-Rosenberg, on the other hand, holds a nuanced position: “There is a perception that women are more participatory, that they are oriented towards cooperation, that they listen more... I think a lot of this is actually stereotype,” she says. “What is very important is that [women] can put on the agenda issues that specifically address other women that a man would not.”

To her Croatian colleague Marijana Puljak, the question of greater female participation in public affairs is not about introducing an alternative type of values to politics, but rather bringing forward topics that men cannot put on the table. “Women should get involved in all aspects and topics that concern good governance and give their view on topics concerning women, like domestic violence,” she says. Zeynep Dereli shares this view: “Research indicates that whether a legislator is male or female has a distinct impact on their policy priorities, making it critical that women are present in politics to represent the concerns of women and other marginalized voters and help improve the responsiveness of policy making and governance.”

When I was Minister of Defence, the only comments I heard were about the size of my earrings and about what kind of lipstick I was wearing.

Quotas or no quotas?

One of the topics that divides opinions among liberal female politicians in the region is the matter of quotas for representation. In short, most of them do not believe they should be imposed – at least not permanently, but for pragmatic reasons are ready to support them until at least basic gender parity has been reached. “As a liberal I am against quotas, even though they are a kind of positive discrimination and they are necessary in a society like ours. But I think they can be useful by allowing women to show their potential in institutions,” says North Macedonian Monika Zajkova. Marijana Puljak, however, wants to hear nothing about quotas: “I believe that you need to promote people to parliament who are good, who have experience, who want to do that job, and not just based on their gender,” she says, adding that the path towards better female representation goes through the education of young people. “Tell them what politics is, tell them how to organize themselves, how to present the positions they stand for, how to change things, and how to educate them from the ground up,” she concludes.

On the other side of the spectrum is a person who unequivocally backs quotas, a Turkish politician from the DEVA party, Zeynep Dereli. “I believe that we need positive discrimination. We need quotas until we reach the state where we do not need quotas. Especially for countries like Turkey, we need it,” she says, adding that she believes that the more women in politics, the greater the tangible gains for democracy, including greater responsiveness to citizen’s needs, increased cooperation across party and ethnic lines, and more sustainable peace.

Even politicians who back quotas, however, have little illusion about what they can attain in the toxic political environment of the region. Diana Topcic-Rosenberg, for one, thinks that even though quotas are needed, they can be harmful to female empowerment if they are designed to let parties simply tick boxes. “It is good to have a quota system because it does force parties to put forward an equal number of men and women and give them a chance to fight for political positions. However, just by itself, it is window dressing,” she notes. Or, as Tinatin Khidasheli puts it eloquently, “it is the culture of politics that has to change, not simply the numbers.”

The importance of a good example

If there is one thing that all #FemaleForward leaders can get behind, it is the fact that getting more women involved in politics is for the public good and that they have a role – as role models – to inspire the next generation of female leaders. “By entering politics, I wanted to be a role model for my generation of young women, to show them that even if it is not easy, we can do a lot for society,” Monika Zajkova says. “Let’s just do the things that are worth doing, and actively encourage other women to take a lead. Self-confidence is so important – women don't have to look at themselves through the mirror of a certain cultural path or prejudices that come from the past. They should be looking at the mirror, seeing themselves today, and looking at the future, because they are building it,” her Romanian colleague Ramona Strugariu thinks.

For this Romanian MEP, the role of today’s female politicians is not only to serve as examples, but also to point out the structural problems that prevent more women from joining politics – and public life in general. One such issue she singles out is the lack of paternal leave in many societies, which makes it obligatory for women to stay at home and leave their careers once they have children, but there are many others issues we could add, some legal, some purely cultural.

“This is where we, as liberal and, in particular, female politicians, should be going,” says Diana Topcic-Rosenberg. For her, it is about creating a space for women to be perceived not simply as someone with a domestic role, but also with a general social role as well. “Actually, this is one of the reasons that propelled me into politics – I didn't want to allow the silencing of women who happen to think differently,” she concludes.

In order to help aspiring female civil leaders get out of the silence, the ALDE Party has moved on to transform the EWA academy into an even broader initiative, The Alliance of Her. It aims to expand the reach of its world-class academies to more talented and ambitious liberal women at all stages of their political journey, to build a network of female political leaders, and to work towards the removal of barriers to female political participation. Such support is invaluable if we want to see progress beyond the “snail’s pace,” as the ALDE “Ignite her ambition” report concluded. Or, as the Vice-President of the European Commission Margrethe Vestager said, “We still have a lot to do when it comes to the equal representation of women and men in politics. This is a core value for us as liberals and social liberals, and to see it achieved in practice is essential.”

Follow more stories and analyses on female empowerment with #FemaleForwardInternational and in our Special Focus on the website.

This analysis is included in the #FemaleForwardInternational Publication.