Educación

The urgency of quality education for girls and women in Latin America and the potential of technology to achieve it

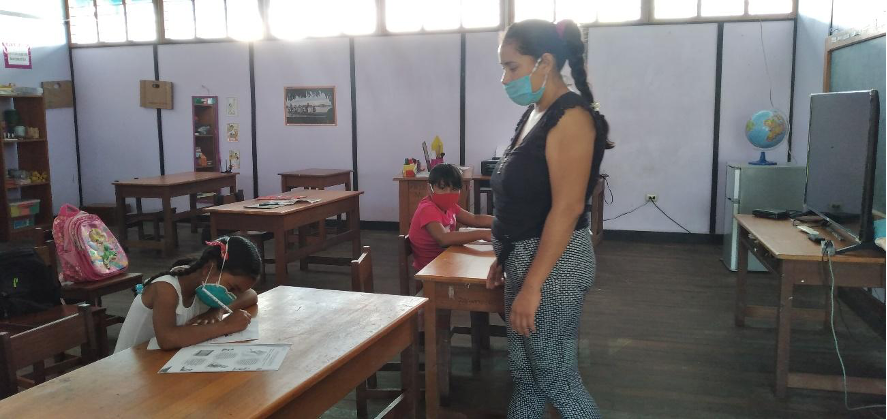

Profesora de Ucayali con estudiante

© Más-EducaciónEducating girls and women, in addition to being a human right, represents a benefit to all of us because it contributes to reducing inequality and poverty as well as strengthening democratic citizenship in the countries. However, today in the world, there are 129 million girls without the possibility to be educated, and those with access to school face considerable barriers to completing it. How can we strengthen girls' access to quality education in Latin America? Education with technology has proved to be an answer to achieve this if certain essential conditions are fulfilled.

In this article, I will present the current context of the education of girls and women in Latin America and Peru, explaining the obstacles they face to access quality education and why they must overcome them. Furthermore, I will argue that education with technology can be a powerful tool to close the gender gap and empower girls. Finally, I will present evidence-based recommendations to implement EdTech projects that could impact girls' and women's education.

Girls' right to quality education

Education is a fundamental human right for everyone, regardless of who they are or where they come from, as is stated in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The fundamental cycles of education (initial, primary, and secondary) must be compulsory, guaranteed, and have public investment available to everyone.

However, according to UNESCO, it is estimated that 129 million girls in the world between 6 and 17 years old do not attend school[1]. That amount is equivalent to the sum of the entire population of Colombia, Argentina, and Peru. It is in the poorest countries of the planet, several in Africa, where most girls without access to education are found.

Regarding Latin America, except for poor countries like Haiti, in 2019, almost 100% of girls between 6 to 10 years old had access to primary school education. However, girls’ right to education is not only to allow them access to schools but to give them opportunities to complete their fundamental cycles of education. This has not been possible in Latin America yet. In 2019 just 65% of girls finished secondary school (11 to 14 years old), and less than 50% completed high school (15 to 17 years old).

[1] https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/girlseducation#1

UNESCO. GEM Report. UIS database. 2019.

Moreover, it is estimated that the number of girls out of school has increased due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Although there is no consolidated data yet, the Plan International organization conducted surveys among girls and women in 14 countries (including 3 in Latin America), where it was found that the main pandemic negative effect identified by 62% of the interviewed was "not being able to go to school or university."[1] Additionally, in countries affected by fragility or conflict, girls are 2.5 more likely to be kept away from education than boys.[2] Therefore, we can deduce that due to the COVID-19 pandemic, girls' access to education has been reduced.

Finally, girls not only have the human right to go to school but to receive a quality education. This is confirmed in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), specifically in SDG 4, which countries have committed to achieving by 2030. SDG 4 says that countries must "ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all."[3]

Ensuring a quality education for girls implies that they have well-prepared and professional teachers and enough resources to achieve learning. It is also necessary that they feel safe in their schools and educational spaces, that they acquire skills and knowledge to integrate and compete in the labor market, and that they develop the necessary socio-emotional skills to navigate

[1] Plan Internacional. Vidas detenidas: El impacto de la COVID-19 en niñas y mujeres jóvenes. 2021.

Why don't girls have access to education?

The reasons for not allowing girls access to education differ in each country and community. Based on the barriers identified globally by the World Bank, I will present some that affect the Latin American region with examples from Peru.

It is one of the most determining factors for girls not being able to access and complete their education. Girls from poor or extremely poor contexts, who live in rural or remote areas or belong to an ethnolinguistic minority, are often delayed in or unable to access education. For example, the secondary school completion rate in 2019 in Peru for adolescent women in rural areas was 62.4%, and in extreme poverty context was 47.9%, while in urban areas was about 81.7%.[1]

[1] Encuesta Nacional de Hogares del Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática. Perú. 2019. Website: http://escale.minedu.gob.pe/ueetendencias2016

Thousands of girls in this region are victims of violence on their commute to and from school. Girls who have to walk several hours in rural areas and those who take public transport in urban areas, all of them are exposed to harassment and sexual abuse on the way to their educational centers. For example, in Peru, in 2022, "every day, 16 girls and adolescent women are victims of sexual abuse,"[1] says UNICEF. And between 2013 and 2022, the SíSeVe school violence reporting system informed about 22,744 physical, psychological, and sexual violence cases against adolescents and women.[2]

Violence seriously affects girls' physical and mental health, leading them to reduce their attendance at school, abandon their education and cause their families to not send them to school because of fear. Sexual abuse and sexual exploitation can result in teenage pregnancies; for example, between 2020 and 2021, the cases of mothers under 15 years of age in Peru increased from 1,158 to 1,438.[1] Girls who become mothers are usually victims of stigma and discrimination in their families and communities. The consequences of this can lead girls to drop out of their studies.

[1] https://peru.un.org/es/178888-ante-los-casos-de-abuso-sexual-contra-nin…

[1] https://peru.un.org/es/178888-ante-los-casos-de-abuso-sexual-contra-nin…

In many Latin American families, boys' education is prioritized over girls', especially in households where the resources to cover school expenses (transportation, materials, uniforms, etc.) are limited. For example, in MásEducaciónPe, we collected the testimony of a teacher from Pomacancha[1] (a rural area in Junín, Peru) who told us that he had to persuade families to allow students to continue their distance education during the pandemic. The families preferred that girls spend their time helping with housework and harvest activities rather than studying. This obstacle inside the house stops girls from completing their education.

[1]https://mas-educacion.pe/2020/10/21/la-gestion-comunitaria-del-profesor…

From classrooms to other spaces inside schools, there is a reinforcement in messages that affect girls' aspirations and well-being. For example, in Latin America, from a very young age, many girls hear teachers say that "women are not as good at mathematics as men," which excludes them from STEM disciplines as professional options. Likewise, the spaces of many schools do not contemplate specific women's needs, for instance: menstrual hygiene; for this reason, girls feel uncomfortable and do not want to attend school.

The worst-case scenarios come true when several obstacles coexist in a single context. Studies show that, in deep poverty conditions, barriers are more significant.[1]

Why is it beneficial for everyone to educate girls?

Besides education being a human right, reducing the gender gap in terms of education brings economic, social, and political benefits to a country.

Firstly, educating girls reduces poverty and inequity in countries because it allows women to integrate into markets, contributing to the country's economy. Studies have proven that poverty affects women more than men, and depriving females of opportunities also affects society's development. Therefore, education and development opportunities for girls will benefit not only women but also men. One estimates that reducing the gender gap in education can bring around 112 and 1522 trillion dollars annually in developing countries.[1]

Secondly, quality education is essential to strengthen democratic citizenship, live in community, and avoid conflicts. An investigation published by One calculates that the potentiality of conflicts could decrease as much as 37% if quality education is provided to men and women.[2]

Thirdly, girls who complete their fundamental education are less prone to teenage pregnancy. They tend to live healthier and more productive lives. Girls with access to formal education are more likely to use contraceptives, marry at later ages, have fewer kids, not contract HIV, and be better informed about their kids' nutritional needs.[3]

Lastly, women with quality education are inclined to have better salaries and make their life decisions, resulting in a greater future for themselves and their families. Nowadays, Latin America has a 53% female participation rate in the working market (under the men's participation rate).[4] Having more educated women stimulates the labor market.

[1] https://www.one.org/us/issues/quality-education/

[2] https://www.one.org/us/issues/quality-education/

[3] https://www.worldvision.ca/stories/education/girls-education-facts-and-…

Can technology be a solution to educating girls?

Access to technology has widened now that we are overcoming a global pandemic in which girls and boys had to learn from a distance and integrate technology into their lives. This allows us to imagine technology as a vehicle to reduce the gender gap in education. Latin America reached 500 million users connected to the internet from a smartphone at the end of 2021, and by 2025 the percentage of the population adopting this practice is expected to rise to 80%.[1] Therefore, access to this technology could be used to enhance girls' education.

Nevertheless, access to connectivity and devices does not guarantee quality education. Examples such as the One Laptop Per Child in 2007 and the Aprendo En Casa strategy in 2021 (when a million laptops were handed in Peru) proved that the enhancement of education by technology requires more than providing laptops or tablets to students.[2]

[1] https://www.gsma.com/mobileeconomy/latam/

[2] GRADE made a study called One Laptop per Child at Home: Short-Term Impacts from a Randomized Experiment in Peru that showed that the introduction of XO laptops did not achieve the desired impact since it lacked a teacher strengthening pedagogical strategy Web: https://www.grade.org.pe/publicaciones/one-laptop-per-child-at-home-short-term-impacts-from-a-randomized-experiment-in-peru/ On the other hand, the effect of the 1 million tablets handed to students in 2021 as part of the Aprendo en Casa strategy has not yet been evaluated, but Minedu already presented the Estudio Virtual de Aprendizajes 2021 paper where students have reduced their learning achievements at very high levels; hence, we can deduce that tablets did not have a significant impact in mitigating learning. We have to wait for a study to confirm it, but I venture to this deduction, given the design of the strategy and the current data.

La tecnología empodera a las niñas y mujeres en su educación formal y en varios otros aspectos de la vida

Education with technology can strengthen the education of girls and women. In addition, evidence shows that the involvement of girls and women with technology helps the learning process and empowers them. Though, certain conditions need to be implanted to achieve the desired impact.

EdTechHub[1] examined evidence from 39 worldwide studies about girls and EdTech (education with technology),[2] and they found that:

- When girls have full access to EdTech and barriers are removed, they respond to technology with a higher degree of participation and involvement than boys. For instance, in Kenya, girls significantly increased their reading level by integrating an app, surpassing boys.

- Full access to EdTech also proved to be of higher impact in the empowerment of girls and women than it is for boys and men. For example, multiple African alphabetization projects used mobiles (mobile-assisted literacy learning) to help girls and women comprehend readings in languages they could not understand.

- Technology not only empowers girls and women in their formal education but also in other aspects of their lives. To illustrate, an Online and Distance Learning project in India enabled women to widen their economic possibilities, health decision-making abilities, and understanding of their rights.

[2] Webb, D. Barringer, K. Torrance, R. Mitchell, J. (2020). Girls’ Education Rapid Evidence Review . EdTechHub. 10.5281/zenodo.3958002

However, the benefits of education with technology for quality education and empowerment for girls and women will only be possible if a) equitable access to technology is given to girls and b) there is an educational context ready for a comprehensive transformation.

On the one hand, studies demonstrate that non-equitable access to technology for girls is one of the most significant barriers to overcome. Many schools do not have the resources to assure equitable access and the ones that do have them hold authorities or teachers that are gender biased, which impedes equitable access.

According to learned gender roles and standard practices, schools privilege access to technology to men rather than girls. The same occurs in other social contexts, like access to devices at home. Families limit girls' access to technology because of traditional gender roles, causing them to learn these limitations and restricting their confidence to use and explore technology.

On the other hand, there is a need for an educational context ready for a comprehensive transformation. Firstly, teachers' personal development should be trained and fortified in terms of technology integration and teaching strategies capable of facing specific gender needs. Secondly, schools' syllabus and pedagogy strategies should be transformed to integrate technology and eliminate discrimination against girls and women. This is because, unfortunately, in many countries, gender biases remain in the content and ways of teaching in schools. Thirdly, the presence of authorities and educational policies that prioritize investment in the education of girls and women is necessary.

Final words

- The girls’ and women’s access to a complete and quality education is a human right.

- Girls around the world experience multiple barriers to accessing quality education. Poverty, violence, cultural aspects, and inequity in schools are problems that stand out in Latin America.

- Educating girls and women is urgent. Besides education being a human right, reducing the gender gap in terms of education brings economic, social, and political benefits to a country.

- Education with technology can strengthen girls' and women's education. Evidence shows that the involvement of girls and women with technology helps the learning process and empowers them.

- Equitable access to technology for girls and an educational context ready for a comprehensive transformation are two essential conditions needed to reach an education able to impact the gender gap positively and empower girls and women.

About the author

Author: Carla Gamberini Coz

CEO and co-founder of MásEducaciónPe

Director of Mangahigh in Latin America and Spain

Carla Gamberini

CEO Más-Educación

© Más-Educación