Disinformation

Visit Program FNF in Brussels: Defending Freedom and Democracy

In many Latin American countries, journalists work under dangerous conditions. In 2022, Mexico was classified as the most dangerous country in the world for journalists.

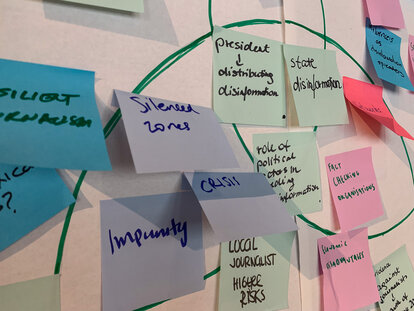

Over the past years, the great danger posed by disinformation and foreign interference in elections and democracies worldwide has become clear. Public discourse, a fundamental pillar of democratic states and societies, is weakened by selective manipulation that hinders independent information. Civil society and antigovernment actors in numerous countries face daily challenges in their fight for the rule of law and political diversity.

In the Philippines, widespread disinformation campaigns and online propaganda significantly contributed to the electoral success of former President Rodrigo Duterte and his autocratic government. Similarly, there is a long history of election-related disinformation spread by anonymous news portals and state actors in Mexico. According to Reporters Without Borders, many Latin American countries have journalists working in hazardous conditions, with Mexico ranking as the most dangerous country for journalistic work in 2022. More than 12 journalists were killed that year, representing almost 20% of the worldwide deaths of journalists. The proliferation of digital and social media has exacerbated the disinformation problem, especially in countries like Ecuador.

However, disinformation knows no boundaries. For example, the political discourse surrounding disinformation has permeated considerable European political arenas. For this reason, FNF Europe hosted an international delegation in Brussels in April to connect them with European partners working on combating disinformation. This delegation, composed of disinformation experts, met with representatives from European Union institutions such as the European Parliament and the European External Action Service, as well as associated liberal organizations (European Liberal Forum and LYMEC) and other civil society organizations in Brussels working on monitoring and combating disinformation and foreign interference. A public event titled "Defending Freedom and Democracy: The Global Struggle of Liberals against Disinformation" was also organized, where delegation members took part as speakers, reinforcing exchanges with Brussels' political audience and sharing mutual experiences.

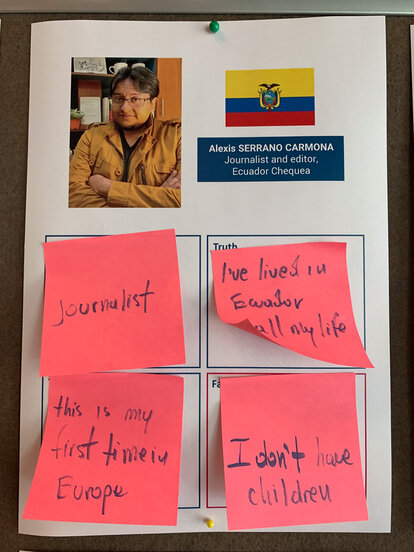

Brussels Delegation

Participants in this visit program confront the dangers and challenges of state-sponsored disinformation and the lack of an independent mechanism to protect them.

At the end of the program, participants stated that while they expected similar disinformation situations in Mexico and Ecuador, they were surprised to observe similar patterns of disinformation in the Philippines. These patterns include the involvement of high-level political actors in creating disinformation narratives, which are transformed into media products with the help of influential figures—often paid—and then disseminated as fake news. As journalists and human rights advocates, all participants in this visit program confront the dangers and challenges of state-sponsored disinformation and the lack of an independent mechanism to protect them. Thus, the program allowed participants to share best practices with their European counterparts and among themselves.

Existence of True Disinformation Networks, Systematically and Intentionally Engaged in Producing Lies and Manipulation

Disinformation: The Brussels Experience

Written by Alexis Serrano Carmona

Recently, I defined myself as a heretic converted to fact-checking. I am not a big fan of labeling journalism, and fact-checking is one of the constitutive muscles of the profession, one of its cornerstones. That is why considering fact-checking as an extraordinary activity, far from the daily life of journalists, seemed absurd to me. However, my experience as the editor of Ecuador Chequea has allowed me to see the situation from a different perspective. Although I still think the same, the levels of disinformation are so numerous and dangerous that it is right to give fact-checking the importance it deserves.

With this experience, I have confirmed, as evident as it may seem now, genuine disinformation networks are systematically and intentionally engaged in producing lies and manipulation. Faced with this, as we often say in the newsroom, the more containment walls we can place against these disinformation networks, the better.

In Ecuador and based on my experience in the rest of Latin America, political disinformation (which always prioritizes local politics) is the most common, but it is not the only one.

The experience of the Brussels visit programme on disinformation, organised by the Friederich Naumann Foundation, has helped me to look very deeply into these criteria and to look at the issue from an even broader perspective. To begin with, I was very surprised to see how strongly geopolitical a view of disinformation is taken in Europe. It is a somewhat different experience from what we have, for example, in Latin America. From what we saw in the public bodies and organisations that presented their papers during the tour, I can infer, first of all, that these actors see only one person - or one government - as the 'great disinformer': Vladimir Putin, the president of Russia; and the whole theory and fight against disinformation revolves around him. However, I see this more as a political objective than a real journalistic exercise. The aim, in that case, is to see which geopolitical narrative prevails over the other. The same impetus with which the European Union and the United States try to make their discourse prevail over the Russian one can be shown by Russia to make its own prevail over that of the United States or the European Union.

In Ecuador, and from my experience in the rest of Latin America, political disinformation (which always focuses primarily on local politics) is the most frequent, but it is not the only one. At Ecuador Chequea, we fact-check false earthquake predictions, companies using the image of journalists or public figures to promote fraudulent investments, and more. However, some things we discussed apply to any territory and are essential. For example, polarization is the perfect breeding ground for disinformation.

Fact-checking is an essential activity of journalism in the present and a societal activity for the future.

The main lesson I took from this experience arose from a question we were asked on the program's last day: Is it worth continuing fact-checking in a world where disinformation spreads at an exorbitant speed, likely to increase with artificial intelligence?

One possible answer: pre-bunking as a replacement for debunking. We discussed the levels in the fight against disinformation, and most of us are acting at the defensive and containment levels. Nevertheless, a question arises: saying 'this is false' is no longer enough, they told us. We must shift to the offensive and give social media users the tools to detect disinformation and cut its chain. In that sense, the role of journalism is more important than ever. As a newsroom leader, I plan to focus our efforts on that direction: being vigilant about topics that could generate disinformation and acting before the disinformation networks. I think that could be the way forward.

Another critical point is the dangerous trend of trying to place journalists and the media as possible disinformation actors, however minimal it may be. This discourse of trying to position the false idea that disinformation can come from the media has already led to attacks on the press in Latin America and has served authoritarian governments to promote their narratives and policies against freedom of expression. Journalists and the media stand precisely on the opposite side of disinformation, and strengthening journalism and the press should be a priority for every society. It is essential to clarify certain concepts: having an editorial line is not disinformation, and even making a mistake is not disinformation. Disinformation entails systematic INTENTIONALITY to produce lies and manipulate facts and data. If we do not understand this, we run the risk of governments, international organizations, and other actors claiming the authority to decide which media or journalist is good or bad based solely on whether they say what they want to hear or not. That is precisely where censorship begins.

Considering all these factors, and unfortunately, because disinformation networks are unlikely to yield ground easily, fact-checking is an essential activity of journalism in the present. It will be a societal activity in the future. Now is the right time to generate a debate about how it should be done going forward, and I believe the program we experienced in Brussels was fundamental for this discussion.

Formation of networks to combat disinformation as the primary mitigation action

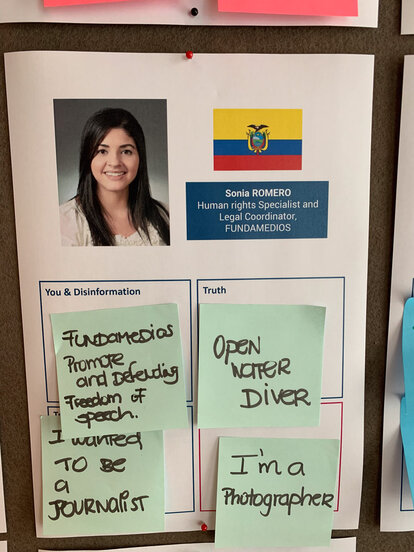

On My Trip to Brussels

Written by Sonia Romero

The trip to Brussels allowed me to identify that one of the most critical topics in the European Union, considering the context of the Russia-Ukraine War, is the upcoming 2024 European Parliament elections. Moreover, I learned that mitigation is prioritized among the main actions taken. Organizations focus not only on fact-checking but also on raising awareness and providing training to citizens on topics with higher flows of disinformation, such as climate change, elections, and migration.

We also found that the main actions taken by European institutions involve checking possible disinformation actions by Russia, China, and the United States to destabilize the European Union. One practice that can be replicated is the formation of networks to combat disinformation, which brings together political actors, media outlets, journalists, academics, and others. It is one of the critical actions for mitigating the fight against disinformation.

During the visit, participants shared their impressions and the experiences they gained from their stay in Brussels.

Programa de visitas FNF Europa- Bruselas

© Fundación Friedrich Naumann para los Países Andinos