#Education

Girls prevented from being bright and dreaming: What can be done through education in schools and at home?

Girls prevented from being bright and dreaming: What can be done through education in schools and at home?

When I was a little girl my grandmother taught me that I was capable of being anything I dreamed of being. However, my grandmother did not know that the fact that I was a girl already limited me in what I could and could not dream of for my future. While my grandmother's message helped me grow up confident in my abilities, perhaps if she had known that the scope of my dreams was already limited, her teaching would have been different and I would not be an educational specialist but a space engineer today.

From the age of 6, girls begin to believe, according to what society tells them, that they are not bright and that disciplines "for the most intelligent" are out of their reach. For this reason, today the world has a scarce presence of women in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) disciplines.

In this article I explore what the stereotype of brilliance is, how it is acquired, and how it potentially impacts women's decisions about STEM disciplines. I also propose four ways to combat this stereotype from homes and schools by encouraging girls to build the skills and referents necessary for them to see themselves as bright, to dream of conquering disciplines "for the bright," and to be successful in fulfilling their dreams.

Women are not brilliant: the stereotype of brilliance

When we think of the general management role in an engineering company, do we think of a man or a woman in that role? And, when we imagine a technology creation space for the development of the new iPhone or the Google offices in San Francisco, do spaces with more men or more women come to mind?

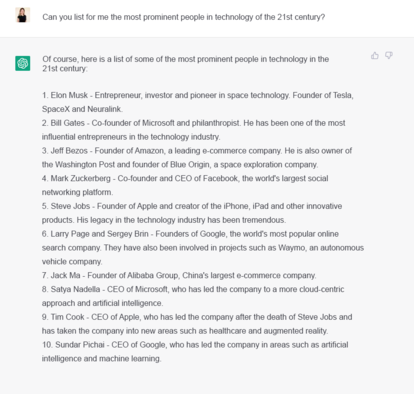

Most people in our society think of men in both cases, and although in recent years women are leading actions and spaces that are slowly contributing to change this perception, there is still a long way to go to change the association of these types of roles to men. Even brand new technological tools such as Chat GPT (based on AI) provides only men's names when you ask for a list of prominent people in technology in the 21st century (see images) because this tool replicates the existing biases in the information on the Internet.

But why are science, engineering or technology professions associated with men more than women? Studies show that this goes back to the stereotype of brilliance. STEM professions are seen as demanding greater intelligence or brilliance and our society associates brilliance more with men than with women. That is, people commonly believe that "brilliant = male".

Although this association does not match reality, it has become so pervasive in homes, schools and workplaces that it keeps women from performing successfully in STEM disciplines in school and keeps them from choosing professions or jobs in these areas because they are perceived as "only for the bright."

For example, studies have shown that there is a stereotype in society that men are "smarter" than women in mathematics, and this stereotype is detrimental to women's performance in this area, while negatively affecting their interest in professions that require high mathematical skills. However, this common belief not only links specific cognitive abilities in mathematics (say mathematical reasoning or problem solving) to men, but also the entire cognitive ability. That is, it is commonly assumed that intelligence or brilliance as a complete ability is more often present in men than in women and that is why they are better at mathematics.

Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash

From the age of 6, girls may have their dreams limited

Like all stereotypes, the "bright = male" stereotype is a social construct, so in order to combat this stereotype it is important to understand more about its acquisition and its impact.

In 2017, researchers from New York University (NYU), Princeton University, and the University of Illinois demonstrated that women and men acquire the stereotype since childhood. Starting at age 6, girls are less likely than boys to associate that people of their own gender are "very, very smart". And, also at age 6, girls begin to avoid engaging in novel activities that are identified as "activities for very smart."

This association of brilliance with men rather than with women, although it does not match reality, determines the ability of girls and boys from the age of 6 to aspire toward goals. In the case of girls, the earlier they acquire the notion that brilliance is not a characteristic of women, the stronger its negative influence may be in limiting their aspirations and dreams.

Such influence may even limit goals and dreams that girls set for themselves throughout their lives, such as their choice of career or job. That is, because girls associate greater intelligence or brilliance with men rather than with themselves, when they grow up they stop aspiring to dreams that are only accessible "to the bright". Among these dreams that are not accessible to them is studying and performing in STEM disciplines because they associate them with constituting very difficult challenges for them who are "not bright".

Figures on women's participation in STEM professions can serve as evidence to understand how much the "brilliance = man" stereotype can influence women's development: worldwide, women represent only 35% of those pursuing STEM degrees in higher education and less than 30% of researchers in science.

It is worth emphasizing that, since 2020, other specific studies have been carried out with racialized girls (black, Latina, indigenous, etc.) that suggest that the impact of the stereotype of brilliance on them is even greater and that the self-perception they form at an early age harms them to a greater degree as it adds to other prejudices they face and limits their development.

Thus we see that, if girls and boys absorb these stereotypes from the age of 6 and act on these ideas, it is likely that many girls who are indeed bright will already have moved away from certain career goals and dreams by the time they reach higher education or the labor market. Therefore, it is critical to take action to break down the "brilliance = male" stereotype in girls from their most familiar spaces in childhood: home and school.

Photo by Robo Wunderkind on Unsplash

Education that fights stereotypes in homes and schools

If mothers and fathers constantly tell their daughters that "mathematics is very difficult" and if teachers in the classroom encourage more boys than girls to use technology, then both spaces are contributing to reinforce the stereotype of brilliance we have been talking about. Even if we do not do it consciously, many of our expressions and attitudes as adults can have an impact on reinforcing stereotypes in the girls around us. Therefore, it is important to make an effort to intentionally promote actions at home and in schools that fight the stereotype of "brilliance = men" and teach girls that they are "very, very smart".

One of the most effective ways to reinforce in girls the belief that they can aspire to develop in "for bright" disciplines (such as STEM disciplines) is to show them brilliant female role models in those disciplines. Both at school and at home, we can create spaces to read, listen to, or watch life stories of brilliant women with whom girls can identify. We can also talk with the girls about these stories and accompany them to dream of scenarios where they could be like these women in the future. For example, "Good Night Stories for Rebel Girls" is a series of books and podcasts (free resource on YouTube) that presents short stories of women from all times and countries who have transformed the world from science, art, politics, economics, etc. The stories are very agile and entertaining and are very easy to integrate into classroom sessions as well as in a family sharing moment at home.

A second way is to provide girls with access to technology both at school and at home. Often in schools, boys are given more opportunities to learn technology skills than girls. For example, in high school, robotics courses are offered to men while women are offered dressmaking and sewing. It is true that sometimes women choose this option; however, we must remember that they have been influenced to make this choice from an early age and we must break this influence by encouraging them to get involved with technology. Also, at home many times if we have only one device, boys are prioritized to use it more than girls (and probably they ask for it less). This reinforces the stereotype and keeps them away from technology. Girls should be encouraged to explore devices and platforms or applications on the Internet, to improve their skills to learn with technology and to accompany them so that they stay safe when they engage in social media..

Third, we can build leadership skills in girls. Both families and teachers can provide emotional support to girls that builds their confidence and self-esteem to lead in ways that allow them to meet challenges. For example, both at home and at school, we can encourage girls to share their thoughts and feelings about different situations by being listened to and valued, to propose ideas for activities to do, and to take the lead in organizing those activities. We can also start talking more with girls about women leaders in their professions or work environments and/or reading them stories about women close to them. A good free resource to read about women leaders transforming their spaces with technology is " Educadoras sin Límites (Educators Without Limits)" (download here). An important part of familiarizing girls with women's leadership is to teach them that women should be recognized in their leadership as brilliant (and not "bossy") as much as men are.

Finally, girls can be encouraged to participate in experiential STEM challenges that allow them to explore and experience these disciplines. For example, encourage their participation in construction projects, science experiments, and programming. These activities can be done as part of school learning sessions as well as part of a fun family experience that brings girls closer to feeling that STEM disciplines are accessible and relevant to them.

Of course, we must not forget that, in addition to these educational actions that can be carried out at home and at school, there are structural barriers such as poverty, inequality, and violence that must be urgently broken in order for girls to receive a quality education that allows them to dream and pursue their dreams.

Conclusions

The stereotype of brilliance associates STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) professions with men rather than women. This stereotype goes back to the mistaken belief that brilliance or higher intelligence is more often present in men than in women.

This stereotype can determine the ability of girls and boys from the age of 6 to aspire to goals.

Girls who acquire the notion that brilliance is not a characteristic of women are less likely to choose STEM careers and are therefore less represented in these fields.

From home and home education, the "brilliance = male" stereotype can be fought by teaching girls that they are brilliant through the promotion of brilliant female role models, access to technology, leadership skills training, and the encouragement of experiential STEM activities.

Fighting this stereotype is critical to removing the barriers that prevent women from performing at their best in all areas and being able to dream and achieve their dreams.

Bibliografía

L. Bian , S. Leslie, And A. Cimpian, Gender stereotypes about intellectual ability emerge early and influence children’s interests | Science (2017)

W. Wood, A. H. Eagly, Biosocial construction of sex differences and similarities in behavior. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 46, 55–123 (2012).

S. T. Fiske, A. J. C. Cuddy, P. Glick, J. Xu, A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 82, 878–902 (2002).

D. Cvencek, A. N. Meltzoff, A. G. Greenwald, Math-gender stereotypes in elementary school children. Child Dev. 82, 766–779 (2011).

S. J. Spencer, C. M. Steele, D. M. Quinn, Stereotype threat and women’s math performance. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 35, 4–28 (1999).

https://shopping.mattel.com/es-es/pages/barbie-dream-gap

S. Upson, L. F. Friedman, Where are all the female geniuses? Sci. Am. Mind 23, 63–65 (2012).

M. Meyer, A. Cimpian, S.-J. Leslie, Women are underrepresented in fields where success is believed to require brilliance. Front. Psychol. 6, 235 (2015).

About the author

Author: Carla Gamberini Coz

CEO and co-founder of MásEducaciónPe

EdTech and Education Policy Specialist

Carla Gamberini

Carla Gamberini

CEO Más-Educación

© Más-Educación