Sahel

Russian influence in the Sahel: Wagner and the support of military juntas

MINUSMA

©United Nations

While in the West we pay special attention to Russia's action on our eastern European border, to the south, in the Sahel, Russia's presence is growing not only in the defence and security sector, but also in social acceptance. This presence has been particularly pronounced since September 2021, when the Malian military junta that has ruled since the May 2021 coup began to realise that it would not hold elections in February 2022.

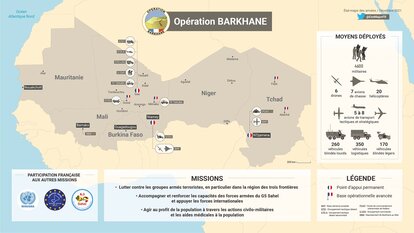

Although the Mali-Russia military agreement was signed in 2019, in December 2021 both Foreign Ministers reaffirmed their willingness to continue the military partnership, especially as France had announced the end of Barkhane a few months earlier. Operation Barkhane is a French counter-terrorism operation that began on August 1, 2014, against jihadist groups in the Sahel region of Africa. It had up to 5100 French soldiers deployed on the ground. During that month, Mali received four Russian military helicopters and approximately 80 % of the Malian armed forces' military equipment is of Russian origin. As late as December 2021, the presence of the private Russian military company Wagner was still being denied at the institutional level, even though in September it had already been leaked that the first talks had taken place to deploy the first 1,000 components of the military contract. Rumours in September were that in addition to providing security for military junta, they would train the armed forces and conduct joint counter-terrorism operations. In December 2021, the presence of Russian military or the private military company Wagner on the territory began to be undeniable, as aerial images of the creation of a military base next to Bamako airport. On 5 January, images appear of the first Wagner/Russian explosive casualty in central Mali, and on the ground, there are rumours of their presence at the military base in Timbuktu in the north of the country.

Inphographic

©CSIS

It is important to note that analysts on the ground are not able to state with certainty whether it is Russian military or Wagner's contingent that is in the different regions of the country, but it is irrelevant as Wagner, like all Russian private companies, is used as an instrument of the government's political, military, or diplomatic projection. According to experts such as the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), Russian private military companies have 16 agreements with Sub-Saharan African governments by 2021. This practice is not only Russian; the same is true of military companies from different countries around the world, such as China. Therefore, despite the denial of Wagner's deployment, for all practical purposes there are proven relationships not only in the Sahelian terrain but worldwide that they are just another arm of Russian military policy.

Because of the presence of Wagner's "mercenaries", relations between France and Mali have deteriorated. Both governments have exchanged hostile statements during the last quarter of 2021, and on 17 February, when Macron finally announced the withdrawal of all Barkhane troops and the Takuba Force (made up of European countries such as Estonia and Sweden) from Mali, he cited as a reason that he would not support a government that hires mercenaries. Apart from the competition for influence at the geopolitical level, one of the reasons why the EU has criticised Wagner's presence in Mali is because of the numerous human rights violations Wagner has committed in other countries such as the Central African Republic, where the UN accuses the group of having tortured, illegally detained and killed civilians. This fear of returning state violence against civilians is beginning to become a reality. This past month, Wagner and the Malian armed forces were accused of having detained and tortured young people in Niono (central Mali) with electrocution, accusing them of being terrorists. During the interrogations, testimonies collected from survivors and recovered by Le Monde Afrique, claim that there was a white man speaking an unknown language, a Malian soldier, and an interpreter. In the same region, 35 charred bodies have been found that have been tortured and several NGOs investigating on the ground have collected testimonies claiming to have seen the armed forces committing these atrocities that have not been seen in Mali since 2018. All these accusations are denied by the Malian armed forces who claim they are fake news.

Moyens déployés

©Gobierno de la Republica Francesa Ministerio de Defensa

Finally, just as in Mali it was Defence Minister Sadio Camara who organised the meetings between the junta and Wagner, following the coup in Burkina Faso at the end of January, several media reports claimed that current President Damiba had asked former President Kaboré to ask Russia and Wagner for help in the fight against terrorism. Apart from these rumours, there is no evidence of such a rapprochement. What is clear is that a section of civil society in the various Sahelian countries, especially those ruled by military juntas (Guinea Conakry, Mali and Burkina Faso), supports the governments having military relations with Russia or its private military companies, especially after their perceived failure of Western international operations. At demonstrations in support of the new junta led by Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba, and demonstrations in support of the Malian junta following ECOWAS sanctions, Russian flags could be seen being waved by young Sahelians. These pro-Russian sentiments have been stoked by social leaders such as Adama Ben Diarra, president of the Yerewolo association, who since 2019 claimed to have asked the Russian embassy to come to Mali to serve as a counterweight between United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) and Barkhane. If Wagner/Russian forces continue to commit human rights violations, this support from societies may be exponentially reduced.

PhD student specialized in violent radicalization in the Sahel and in Europe, researcher and consultant specialized in security, radicalization and conflict management in the Sahel, West Africa and Europe. Analyst associated with the Center for International Security of the Francisco de Vitoria University where she coordinates the Group of Experts Sahel-Europe Dialogue Forum.