AI Education

South Korea slows down on AI education

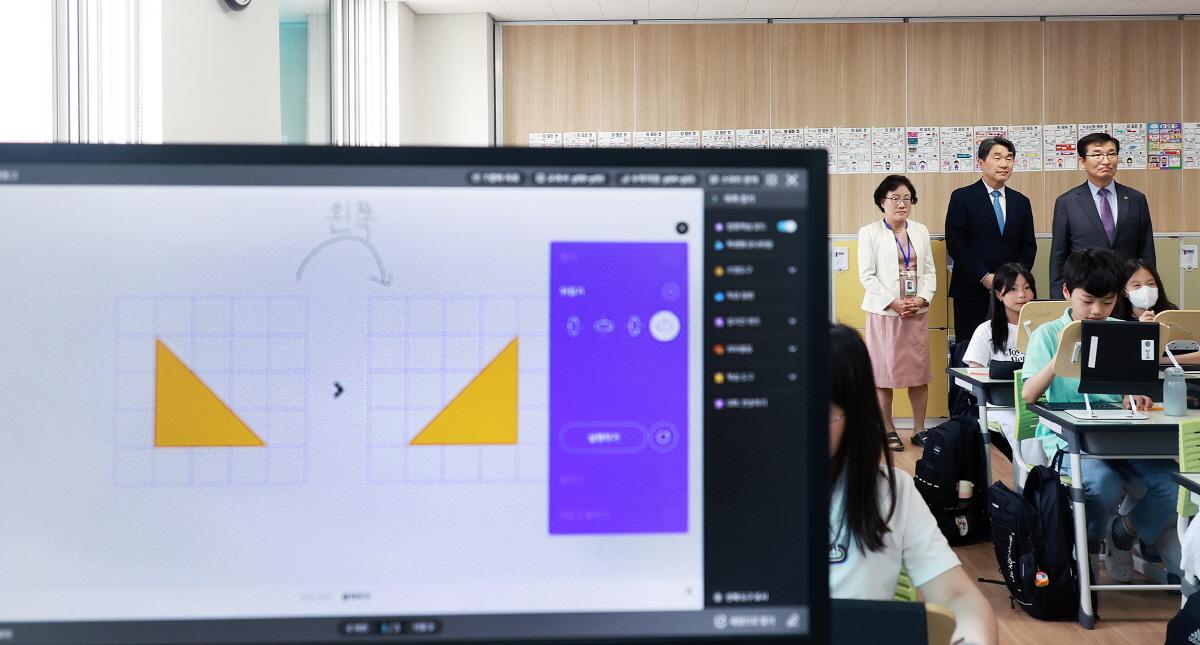

South Korea’s Minister of Education visits an elementary school to observe a class using AI-based digital textbooks.

© Ministry of Education, South KoreaAI-driven education revolution planned

The use of digital AI-supported textbooks was accompanied by high hopes. These digital learning tools analyze students’ learning behavior in real time and provide personalized feedback based on that. As a result, teachers are able to tailor their lessons more effectively to individual student needs. Weaker students receive additional support, while stronger students are challenged with more advanced content.

AI-supported textbooks are intended to increase educational equity and, for example, reduce South Korean students’ dependence on so-called “Hakwons.” Hakwons are private tutoring institutes, which are very expensive and thus disadvantage students from poorer families who do not have access to them.

South Korea’s former President Yoon Suk-yeol and his Minister of Education Lee Juho saw AI textbooks as an opportunity and planned nothing less than a revolution. Starting in 2025, AI-supported textbooks were to be mandatory in elementary and middle school classes in subjects like math, English, and computer science. Lee Juho promised that the AI textbooks would “liven up classrooms” and motivate students to study diligently. School dropouts could also be prevented this way.

Low usage rates despite big plans

However, the plans sparked a major controversy in the country and were stalled by the parliament. According to government data, as of March 2025, fewer than 30 percent of the 6,339 elementary schools used the new AI textbooks. The use was concentrated in English and math, with usage rates between 28.6 and 29.1 percent. Middle schools showed similarly limited numbers, ranging from 26.9 to 23.8 percent. Subjects such as music, art, sports, ethics, and other areas were initially excluded from the rollout.

Lack of preparation, resistance from teachers, and political upheavals challenged the initiative. Given the change of power to the Democratic Party and the inauguration of President Lee Jae-myung on June 4, fundamental changes to AI education policy are expected. The country is now governed by the progressive President Lee Jae-myung, who, unlike the conservative former President Yoon Suk-yeol, is skeptical of AI textbooks.

The reform ultimately failed due to opposition resistance in parliament, which initiated changes to the Elementary and Secondary Education Act. Lawmakers revoked the status of “textbook” from the AI books and reclassified them as “supplementary materials.” The decision about their use now lies with individual school principals who must also finance the AI textbooks themselves.

Teachers are overwhelmed, parents are skeptical

Parents and teachers grew more critical of the project. They raised concerns about rising screen time, data privacy issues, and the risk of students becoming too dependent on digital devices.

A petition initiated by parents against the introduction of AI textbooks gathered 56,505 signatures in May and June 2024. The petitioners pointed to the “numerous negative effects of smart devices” and demanded scientific studies that consider not only learning success but also the holistic development of children. “As parents, we are already facing problems on a scale never seen before, caused by constant use of digital devices alone,” they emphasized.

A survey by the Korean Teachers and Education Workers Union last December also revealed poor preparation of teachers: 98.5 percent of the 2,626 surveyed teachers stated that previous training offers for using AI textbooks were insufficient.

Opposition accuses government of failure

Thus, the AI revolution in classrooms quickly became a political issue. Ko Min-jung, a member of the Democratic Party, expressed doubts about the new textbooks in an MBC radio broadcast: “Since there are concerns about a lack of preparation and possible side effects, we should allow the introduction selectively and only decide after verifying pilot projects whether the textbooks will be used.” However, she believes such research projects were blocked by the conservative government. She accuses the government of catering too much to the economic interests of the Edutech industry.

AI-supported textbooks were a cornerstone of the education agenda of ex President Yoon Suk-yeol, who was impeached in April. Yoon’s declaration of martial law in December 2024 further deepened the country’s ideological divide. The strong polarization in South Korea is also reflected in the dispute over the introduction of AI textbooks.

This is evident in the fact that AI textbooks are more widespread in conservative regions. In the city of Daegu, where former conservative President Yoon received 75.34 percent of the votes, the usage rate for at least one subject is 98 percent. In more liberal regions, such as the city of Sejong, only eight percent of schools use AI textbooks. Usage is nine percent in South Jeolla and 12 percent in Gwangju.

Minister of Education Lee Juho now blames the opposition for the very unequal distribution of the textbooks. Early this year, he feared that educational equality would suffer as a result. Unequal access to AI textbooks would only worsen educational disparities.

With the power transition to the liberal Democratic Party on June 4, significant changes in the system are expected. The reform has so far been stalled halfway; how things proceed is now in the hands of Lee Jae-myung’s party. However, one thing is clear: the public debate will continue, and the nationwide introduction of AI-supported textbooks remains a major challenge. Future reforms should therefore focus on better teacher preparation, targeted investments in infrastructure, longer pilot phases, and equitable access to technology for all schools.

*Zeynep Gezen studies Integrated Korean Studies at FU Berlin and is currently doing an internship at the Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom.