Elections

The Election of the Judiciary in Mexico: What to Expect?

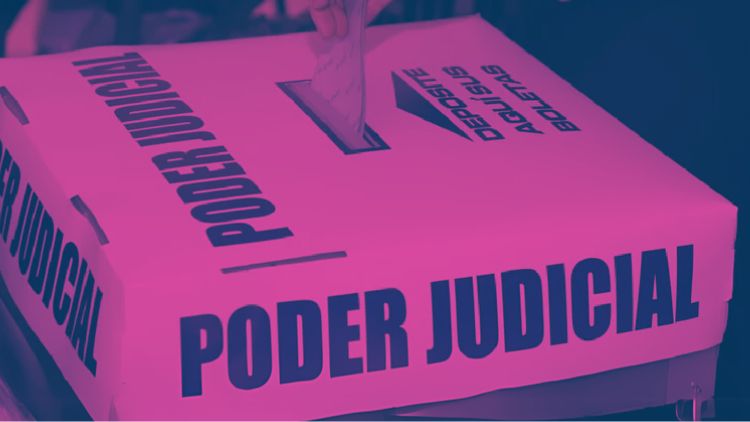

The election of the judiciary at all levels is unprecedented in both Mexico and the world. The reform was first proposed by former Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador in 2023 and became a reality this Sunday, June 1.

In this election, 881 federal positions across various fields were at stake, including the 9 seats for the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation, as well as 1,800 magistrates and judges in 19 states across the country.

In 2027, a popular vote will be held for the remaining positions of district judges and circuit magistrates.

An Election That Failed to Spark Enthusiasm

An Election That Failed to Spark Enthusiasm

According to a poll by Enkoll for the newspaper El País, only 22.9% of respondents said they would vote. In the end, only 13% of the electorate participated, and of those over 20% submitted spoilt or blank ballots.

While the Mexican opposition ran a campaign to boycott the vote and undermine the election’s legitimacy, the reality is that the campaigns had no media presence. In addition, the candidates had no public or private funding; they were allowed a campaign spending cap of 220,326 MXN (approximately €9,984.37), which had to come from each of the candidate’s personal funds.

Additionally, the voting process was complex, involving many ballots and candidates. For example, the 9 Supreme Court seats had 64 candidates on the ballot. Analyzing just those 9 positions would take a person 16 hours if they dedicated 15 minutes to evaluate each candidate.

An Electoral Mechanism That Has Raised Distrust

The standard electoral mechanism in Mexico—where citizens staff polling stations and count votes—was not used in this election. While citizens did help distribute ballots, they were not the ones who counted the votes. Instead, votes were counted by the National Electoral Institute (INE) in its district offices.

This change has generated distrust, as votes will only be counted within government offices rather than by the public. It will also slow down the process, with results expected to take up to 10 days, compared to the same-day results typically seen in regular elections.

Furthermore, the way the judicial election was designed gives 133 of the 3,202 candidates running for 850 federal judge and magistrate positions a higher chance of winning due to ballot design and arbitrary distribution of vacancies, according to an analysis by México Evalúa.

Oversight

Due to low voter turnout, the ruling parties had the opportunity to mobilize aligned voters. This undermines the separation of powers, as Morena currently holds the presidency and majorities in both chambers of Congress and the Senate—and could now gain control over parts of the judiciary.

Additionally, the lack of results and uncertainty generated by the judicial election have fostered public distrust, as reflected in the low turnout. The changes and their impact on Mexico will unfold over the coming months and years.The administration of justice will not be the same—but there is little hope among experts that it will improve. Electing judges by popular vote does not address the root issues in the justice system: how cases are investigated by police and built by public prosecutors. Lack of funding, professional training and efficient processes all play a major role in a system where over 90% of reported crimes go unpunished. That issue is as unesolved as ever, while the very low voter participation in this exercise has not helped the legitimacy of the process