Czech Republic

Between Populism and Pragmatism

Andrej Babis

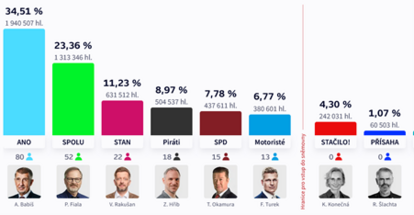

© picture alliance / Sipa USA | SOPA ImagesThe 2025 Czech parliamentary elections represent a turning point in the country’s democratic trajectory. With a strikingly high turnout of nearly 69 percent – the third highest since 1996 – voters reaffirmed their faith in democracy, yet also expressed fatigue with the fragmented democratic camp and frustration over the slow pace of reforms. The populist movement ANO (Action of Dissatisfied Citizens), led by former PM Andrej Babiš, won a decisive victory with 34.5 percent of the vote, consolidating its dominance in 13 regions, except in Prague where they landed second. Despite this, the elections also underscored the enduring resilience of the Czech Republic’s European and pro-Western orientation – a point emphasized by President Petr Pavel.

Babiš’s victory signals a clear shift toward more populist and eurosceptic politics in the Czech Republic. His return to power could bring a more confrontational stance toward Brussels, particularly on the Green Deal, climate targets, and migration quotas. It may also slow the country’s military support for Ukraine, marking a departure from the previous government’s assertive pro-Ukrainian policy. Nevertheless, Babiš’s characteristic pragmatism is likely to prevail - the Czech Republic will almost certainly remain a reliable partner within NATO and the EU, though it is expected to adopt a more cautious and less visible role in regional initiatives related to Ukraine.

Bread, Not Ideology: The Roots of Babiš’s Victory

ANO’s success confirms Andrej Babiš’s enduring political skill and the continued appeal of anti-establishment narratives in Central Europe. By winning 80 of 200 seats, ANO has cemented its position as the central pole of Czech politics. The reasons behind Babiš’s victory lie less in ideology and more in everyday concerns. His campaign centered on inflation, the cost of living, and frustration with elites - topics that resonated with voters who felt left behind.

While former PM Petr Fiala and his conservative SPOLU (Together) coalition focused on security, European leadership, and steadfast support for Ukraine, Babiš spoke directly to the domestic anxieties of “ordinary people,” emphasizing “bread-and-butter” issues such as prices, energy bills, pensions, and “Czech families first.” This contrast between foreign policy values and domestic realism proved decisive. His populist message - part anti-elite, part anti-Brussels - echoed the tone of Donald Trump’s campaigns in the United States. Yet rather than purely ideological confrontation, Babiš blended economic nationalism with promises of managerial efficiency and pragmatic governance.

The vote was also “anti” in nature — particularly anti-Fiala. Many Czechs were tired of the internal conflicts within the coalition, which initially consisted of five parties but, after the Pirates were expelled last year, still had four. The coalition often struggled to agree on vital reforms. ANO successfully absorbed some of the voters not only from the center but also from both political extremes: it drew support away from the far-right SPD (Freedom and Direct Democracy) and the far-left alliance Stačilo! (Enough!), which ultimately failed to cross the 5 percent threshold. This outcome, contrary to earlier polls predicting gains for both extremes, represents a small but meaningful success for democratic stability in Czechia.

The Challenge of Forming a Government

Babiš’s path to forming a government remains uncertain. His only potential partners are two smaller right-to-far-right eurosceptic parties – the Motorists and SPD. Both oppose the EU’s Green Deal, emissions trading (ETS2), and migration quotas. Yet cooperation with SPD could prove unstable due to internal divisions (SPD's ballot for the 2025 election also featured candidates of the Trikolora, PRO and Svobodné parties, a mix of right to far-right parties, united mainly by opposition to migration, the Green Deal, and deeper EU integration, yet divided on economic policy or foreign affars, making their alliance rather tactical), and its radical stance on NATO and EU membership. Any formal alliance with these forces would test Babiš’s repeated pledge to keep the Czech Republic firmly anchored in the European Union and NATO – a red line he reiterated on election night. Nevertheless, Babiš has also expressed his ambition to establish a single-party minority government, relying only on external support from these two parties rather than entering a formal coalition.

Beyond coalition building issues, Babiš also faces renewed legal uncertainty. He is awaiting a verdict from the Prague District Court in a case concerning alleged misuse of European Union subsidies linked to the Stork’s Nest project — a farm and conference center once part of his Agrofert business empire. The case centers on whether the company was temporarily separated from Agrofert to qualify for funding reserved for small and medium-sized enterprises. Following the High Court’s June decision to overturn his earlier acquittal, the lower court is expected to re-examine the evidence. Should the proceedings advance, parliament may be asked to vote on lifting Babiš’s immunity.

A Political Realignment: Conservative Losses, Left-Wing Collapse, and a Record for Women

The conservative coalition SPOLU – composed of conservative ODS (Civic Democratic Party), liberal-conservative TOP 09 (Tradition, Responsibility and Prosperity) and social-conservative KDU-ČSL (Christian and Democratic Union – Czechoslovak People’s Party) – finished second with 23.4 percent and 52 seats. Despite leading the outgoing government, SPOLU’s setback reflects the difficulty of governing through multiple crises: inflation, energy shocks, and social polarization. It also exposed the coalition’s lack of clear communication about its achievements and reforms. Former PM Petr Fiala’s dignified response, emphasizing respect for democratic outcomes and the country’s Westward orientation, stood in sharp contrast to populist rhetoric, yet it could not overcome widespread voter fatigue. Babiš effectively capitalized on this weakness, presenting himself as the voice of those who felt “left behind.”

The centrist STAN (Mayors and Independents) gained 11.2 percent of the vote, while the Pirate Party, running in alliance with the Greens, secured 9 percent. Both reaffirmed their commitment to European values, transparency, and responsible governance but will now take up seats in the opposition. Together, the democratic camp – including SPOLU, STAN, and the Pirates – fell short of the 101 seats needed for a parliamentary majority. Yet while STAN and the Pirates improved their results, SPOLU’s decline suggests that conservative will need to rethink their strategy for rebuilding trust and political relevance.

The 2025 elections also confirmed the continued collapse of the Czech left. The far-left coalition Stačilo! (Enough!) – bringing together the remnants of the Communist Party and other socialist movements – failed to enter parliament. Notably, both the far-left and far-right fell short of their expected breakthroughs, which is a sign that, despite growing polarization, most Czech voters continue to reject extremist alternatives.

Another positive outcome of the 2025 elections is the historic increase in women’s representation. The new Chamber of Deputies will include 67 women, the highest number in Czech history. Thanks to voters giving preference votes to individual candidates, female representatives of the Pirates and STAN advanced significantly, sending predominantly female delegations to the lower house. In contrast, the Motorists and SPD recorded the lowest share of female MPs, highlighting a persistent gender gap between progressive and populist parties.

Navigating Contradictions: Babiš’s Balancing Act Between Europe and Populism

The immediate question now is whether Babiš will govern pragmatically or steer the Czech Republic toward a more illiberal path. It is important not to immediately demonize Babiš and his government or prematurely predict a Hungarian or Slovak scenario. He remains above all a pragmatic businessman, not an ideologue, and is deeply dependent on European markets. No “regime change” is expected in the Czech Republic, and its democratic institutions remain robust. Still, the tone of the new government will matter. A more confrontational approach toward Brussels on climate and migration policies can be expected, reflecting the eurosceptic positions of his potential partners but also Babiš’s focus on defending domestic economic interests.

The Road Ahead: Stability, Responsibility, and Liberal Renewal

Babiš’s victory reflects frustration with the status quo rather than a rejection of democracy or Europe. The Czech Republic will not experience an immediate ideological shift away from Western and European values, but it is likely to enter a more transactional, interest-driven phase of policymaking.

As coalition talks begin, President Petr Pavel’s role will be pivotal. His balanced message after the elections – congratulating the winners while reaffirming the country’s pro-Western direction – reflects the institutional maturity of Czech democracy. In the coming weeks, the key challenge will be to form a government capable of ensuring stability without undermining liberal institutions.

The new political map, with six parliamentary clubs and a record number of parties represented, embodies both pluralism and fragmentation. For liberals, this moment demands a renewed commitment to values-based cooperation across party lines – strengthening the rule of law, supporting Ukraine, defending media freedom, and protecting European integration from populist shortcuts.

In a year marked by political turbulence across Europe, the Czech elections serve as a reminder that democracy is never static. The country’s liberal forces now face a strategic choice: to rebuild trust not through fear of populism, but through the courage of ideas.

Wahlergebnis in Tschechien

© ČT24