United Nations

The UN Charter turns 80 - A Reminder of a Vision

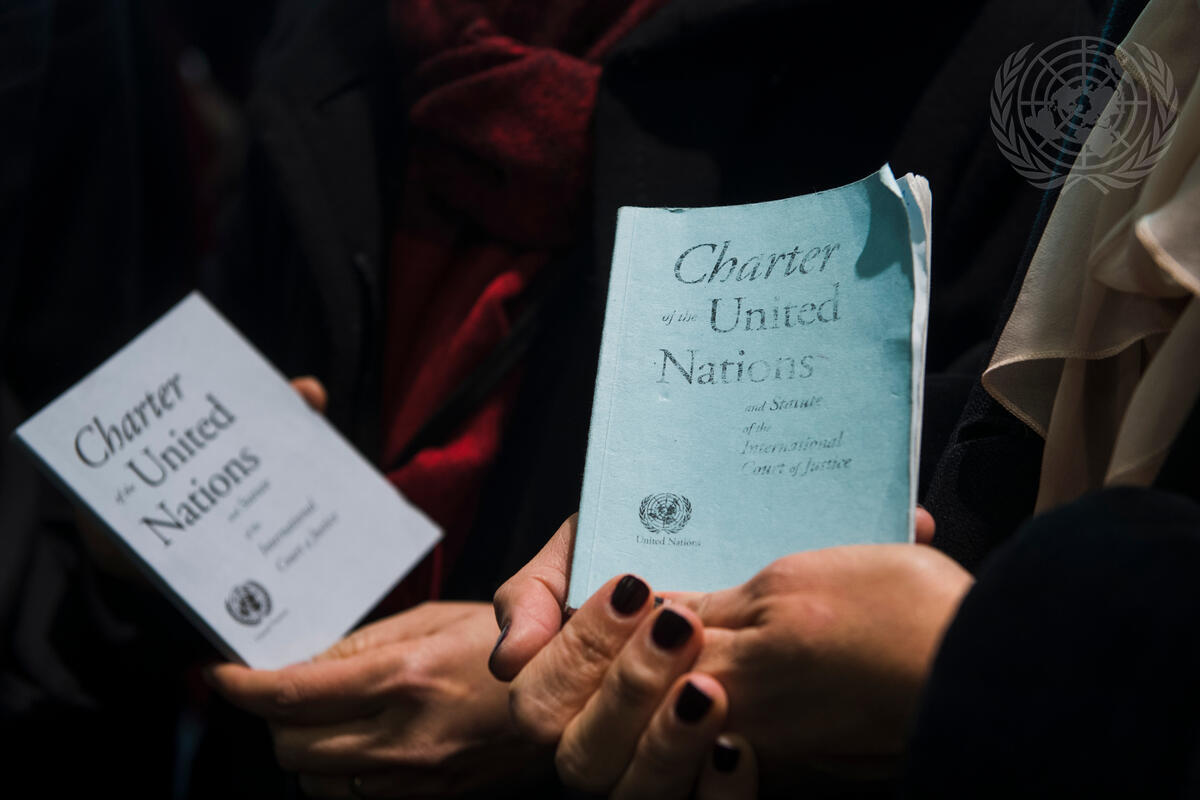

UN Charter

© UN Photo/Amanda VoisardFor its 50th anniversary, Christian Tomuschat, a German international law scholar and UN expert, offered these words of congratulation: “It has become obvious in recent years that the Charter is nothing else than the constitution of the international community (…).” This same description has also been applied to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights.

The 50th anniversary of the UN Charter was tragically timed. It followed just one year after the 1994 Rwandan genocide, where the international community intervened too late to halt the bloodshed. And in July 1995, the Srebrenica massacre occurred. Legal reviews of both these failures by the international community are now available.

Today, the world continues to be shaped by armed conflicts, mass displacements, and severe human rights violations, all contravening the UN Charter. There’s no need to list the widely known current political examples here, but it’s an opportune moment to remember the people of South Sudan. Their plight was a deeply personal concern for Gerhart Baum, a former United Nations Special Rapporteur, long after his mandate ended. In this area, often overlooked by Western media, the national army and ethnic militia groups are engaged in conflict. Over the past decade, tens of thousands have been killed, and hundreds of thousands displaced and forced to flee. There was once hope: when South Sudan gained independence, a peace treaty was signed, and the world's youngest country joined the United Nations Charter in 2011.

Achievements of the UN Charter

From its very inception, the UN Charter embodied the hope for a more peaceful and improved world. Following World War II, there was immense pressure and political will to establish international relations on a new footing and to enshrine international law as a mandatory obligation for state actors.

Thus, the first sentence of the Preamble still reads: “We the Peoples of the United Nations – determined to save succeeding generations from the scourge of war, which twice in our lifetime has brought untold sorrow to mankind,”. The primary goals, duties, and obligations of states include maintaining international peace and security, fostering international cooperation to address global issues collaboratively, and promoting respect for human rights. By joining the UN, states pledge to resolve disputes through peaceful means. The use of force by states is specifically regulated in Article 2(4) of the Charter. The prohibition on the use of force permits exceptions only for individual or collective self-defense under Article 51. However, the Charter’s drafters added that Article 51 is by no means a “natural right” and must be subject to review.

Ultimately, the challenge in political reality is that not all governments of UN member states are genuinely interested in peaceful dispute resolution. This has direct consequences. The Charter, along with its foundational institutions and instruments, can only be as robust as the member states that uphold them. Nevertheless, the achievements of the UN Charter lie in its role as a guiding framework for states, and, crucially, as a universally accepted legal structure. Violations of international law, frequently accompanied by severe war crimes and crimes against humanity, do not diminish the Charter's significance and value. Therefore, the UN Charter, its visions, and its international legal obligations should be recalled not only on anniversaries. It is sufficient to uphold the Charter as a moral compass and an international treaty. It doesn't need to be a constitution for the world community—but it certainly deserves to be taken seriously.