Human Rights

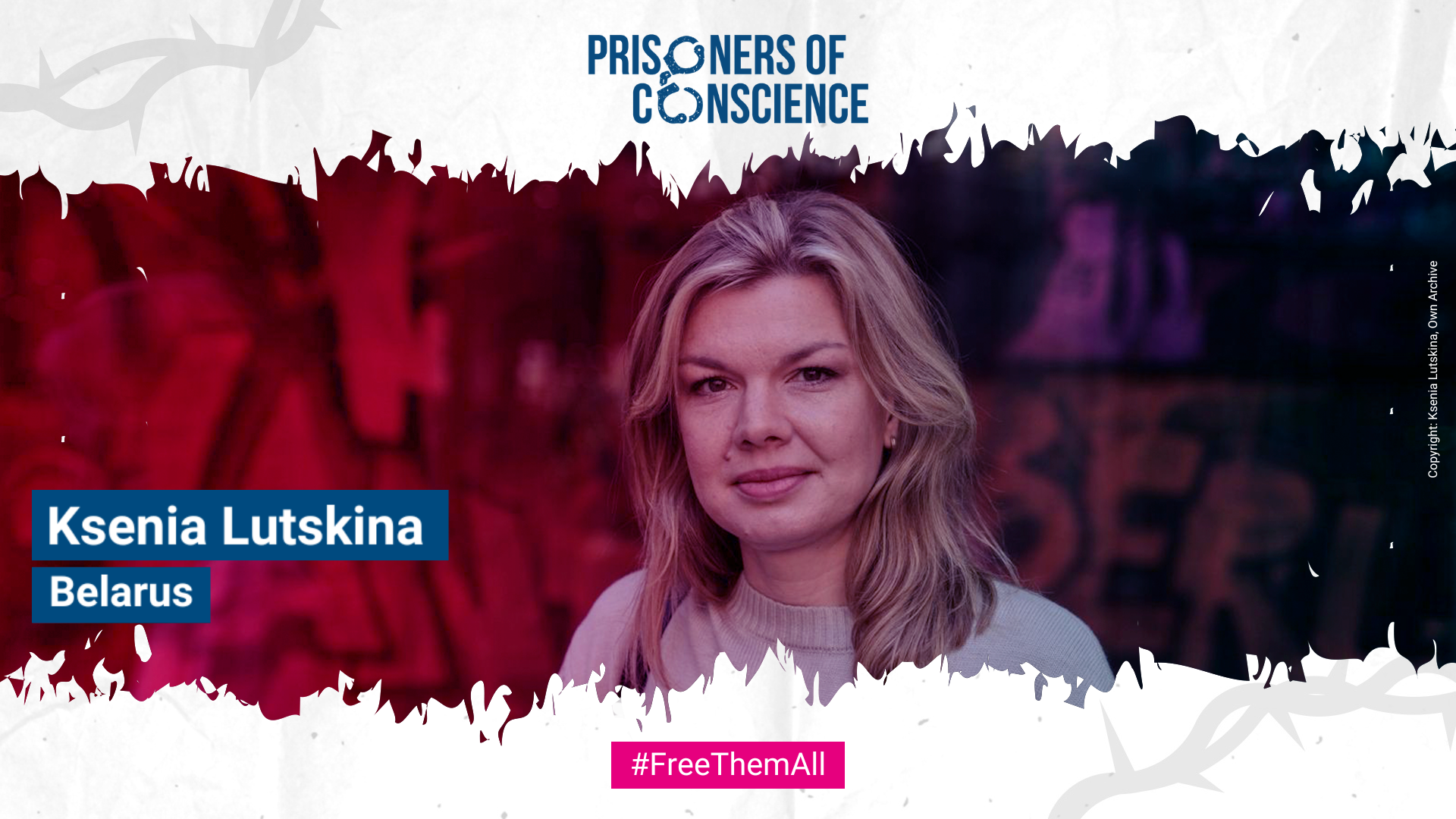

Prisoners of Conscience: Ksenia Lutskina

Ksenia Lutskina was a journalist at the state broadcaster when a wave of protests swept through Minsk, the capital of Belarus. Thousands took to the streets to contest the 2020 election results and demand the resignation of longtime authoritarian president Alexander Lukashenko. Lutskina joined the anti-government rallies and began planning to launch an independent media outlet.

In December of that same year, she was arrested and two years later sentenced to eight years in prison for “conspiring to seize state power.” After serving half of her sentence, she was pardoned and released in the summer of 2024. She now lives in exile.

The interview was edited for length and brevity.

Did you expect to be targeted for your work? Was there a specific moment when you felt you had crossed an invisible line?

On state television, we all knew the rules. We had what I call “the frame.” Inside that frame, we were free — but never outside it. You could have creative projects, but if they didn’t align with the state’s vision, they would be rejected. The most important rule was that you could not criticize the state. You had to agree with everything. Everyone understood these rules, and they were crucial.

I always avoided politics. I didn’t want to work for Lukashenko. I felt my work on culture and history was important — especially against Russian propaganda. Since Russia promotes only Russian history and culture, erasing Belarusian identity, making documentaries about our culture, past, and heritage was vital.

But after the 2020 elections, everything changed.

The most important rule was that you could not criticize the state. You had to agree with everything. Everyone understood these rules, and they were crucial.

What was the atmosphere like inside the broadcaster during that time?

Before the election, the building was occupied by the military and police. Two whole floors were filled with them. It was intimidating, and very stressful. They were there to prevent strikes and control us. We wanted to show the truth, but that was impossible. For three days, there was no internet. On Belarusian TV, they aired old reports about agriculture, culture, and sports — while violence was happening on the streets. People were furious with us, but we had no power to change the broadcasts.

We organized a strike inside the broadcaster. More than 3,000 employees of 18 TV channels and several radio channels demanded to work as real journalists, to report honestly. We even wrote a letter to the Ministry of Information.

I was one of the leaders of the strike, and we decided to create an independent media project online. For me, that was the only way forward. But in December 2020, I was arrested — just before we planned to launch officially on New Year’s Eve. I was accused of organizing a conspiracy to overthrow the government through my independent media platform and later sentenced to eight years in prison.

Looking back, how do you see that period?

2020 was both terrible and inspiring. On the streets, Belarusians saw each other — they realized they were the majority, not Lukashenko. It was a national awakening. Even though I was imprisoned, I still believe it was a turning point for our society.

How would you describe life in prison?

For a while I had no contact with the outside world at all, which was very difficult. In Minsk, during the investigation, we were held in a prison more than 200 years old, with no renovations. Conditions were terrible. There was no hot water, and we could only wash once a week for ten minutes, no matter how many people had to share that time. The food was awful.

Medical care was almost non-existent. I believe I was released only because the authorities feared I might die in prison. The doctors wanted to help, but they had no medicine, no equipment, nothing beyond basic emergency care.

What was the hardest part of prison life?

Being separated from my son. I didn’t see him for two years. That was far harder than anything they did to me.

Did you find ways to maintain a sense of hope during imprisonment?

Hope came from within. Prison is a place without joy, but those who had fulfilling lives before imprisonment—careers, families, moments of success—carried that happiness inside. I tried to remind myself that evil cannot last forever, that one day we will be free.

In prison, I found strength from other political prisoners. Despite the harshness, there was solidarity. We also developed a silent language with our eyes—supporting one another even without words. That solidarity was lifesaving.

The key was to protect our psychological state. Even if the body suffers, the mind must remain human—capable of love and of finding joy in small things. I remember after two years in Minsk, when I was moved to the penal colony, simply seeing the open sky without bars filled me with happiness. Grass, trees, and flowers—things we take for granted became miracles.

Books were also vital. In Minsk, there was a good library, and reading gave us refuge.

In prison, I found strength from other political prisoners. Despite the harshness, there was solidarity. That solidarity was lifesaving.

What do you think people outside Belarus should understand about political prisoners?

The scale of repression. At the end of the Soviet Union, there were about 12 political prisoners per million people. In today’s Russia, it is about three per million. In Belarus, it is more than 140 per million—the highest in the world. And these are only the official cases. Many others live as prisoners in their daily life, unable to work or speak freely.

The world should know that in 21st-century Europe, we have a totalitarian regime where people are jailed for reading the wrong website or liking a post on social media. It is essential to speak about this, to raise awareness among Western and European politicians, and to push for change. Belarus has kind, intelligent people, and they deserve a future.

Now that you are free and in exile, how are you rebuilding your life?

We are just beginning. I finally have time to focus on my health, which I urgently need to do. My son is with me, which makes me very happy. He goes to school, loves learning German, and dreams of becoming a historian or maybe a journalist like me. I hope he can pursue those dreams without ever facing prison.

I also devote much of my time to helping political prisoners still in Belarus. Part of me remains there with them. At the same time, I hope to find stable work as a journalist and to contribute to the democratic movement in exile.

Prisoners of Conscience from East and Southeast Europe

We feature select few prisoners of conscience out of the many in East and Southeast Europe. One political prisoner is one too many.

Find out who the other political prisoners are #PrisonersofConscience #FreeThemAll and in the special Focus on our website.