Women in Diplomacy

Equal Talent, Half the Voice?

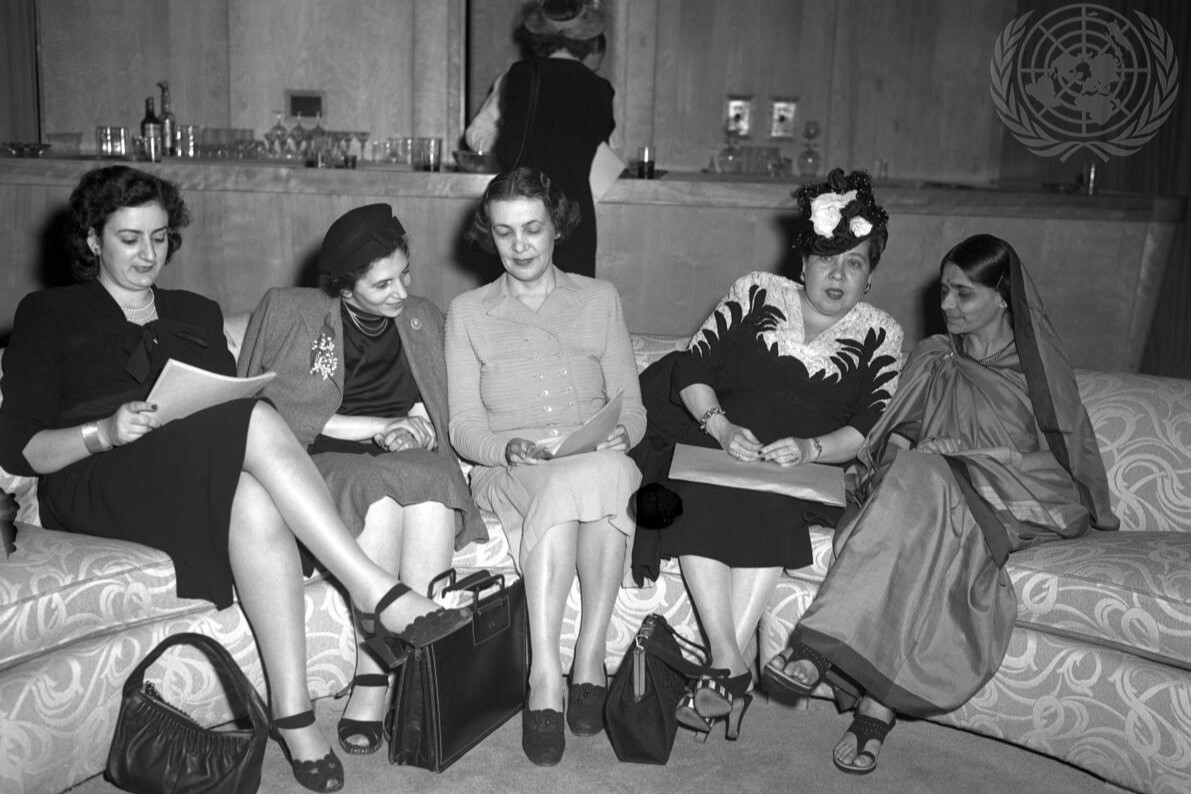

As a finale to their last meeting at Hunter College, the Sub-commission on the Status of Women hold a press conference in the delegates lounge of the gym building. From left to right are: Miss Angela Jurdak, Lebanon; Miss Fryderyka Kalinowski, Poland; Mrs. Bodgil Begtrup. Denmark and Chairman of the committee; Miss Minerva Bernardino, Dominican Republic; and Mrs. Hansa Mehta, India.

© UN PhotoIn a world grappling with overlapping crises, this lack of action is not just disappointing, it’s dangerous. The absence of women’s full participation in diplomacy means missing out on the insights, perspectives, and solutions they bring. Now, more than ever, concrete action is needed to ensure that women are not only represented but fully supported in meeting the unique challenges they face as women in diplomacy.

The diplomat in history

Diplomacy was not always an all-male institution – brocade coats, whispered bargains, and portraits of stern-faced statesmen. But if you look closely, you find women’s fingerprints on treaty parchments long before gender equality became a topic. Prior to the nineteenth century, aristocratic women were regularly involved in European diplomatic affairs, although to a more limited degree than their male counterparts. In 1507, the widowed Catherine of Aragon sailed for England carrying letters of credence that made her an accredited envoy of her father, Ferdinand II of Aragon, empowered to bargain with Henry VII over the timing of her marriage to Prince Henry. Shortly after, in 1529, France’s Louise of Savoy, mother of King Francis I, and Margaret of Austria, aunt of the Emperor Charles V. negotiated the Treaty of Cambrai – so famous for its authors that contemporaries dubbed it La Paix des Dames, “The Ladies’ Peace”. These episodes were exceptions, but they prove that the diplomatic stage has never belonged exclusively to men.

That early promise dimmed during the long nineteenth century. As foreign ministries professionalized, they closed their doors to women except as unpaid, unofficial partners: Their role was limited to being the wives to diplomatic or consular officers. They were expected to run the large diplomatic households, preside as hostesses, make their own contacts to complement the officials work and distinguished themselves by local voluntary and community work – to be charming yet invisible.

Then, in the post-World War II era, as we saw the emergence of international organizations such as the United Nations, which emphasized equal representation and women’s rights, women became more visible in diplomacy. Even then progress was glacial. In 1968, the share of female ambassadors in the world was only at 0.9% according to the University of Gothenburg’s GenDip Program.

Today’s reality: it’s a men’s world

According to the Women in Diplomacy Index 2021, until today, the figure has slowly risen to 21 per cent in 2021, but it varies regionally and between countries. While 41 per cent of ambassadors posted abroad by the Nordic countries were female, only 12 per cent from countries in the Middle East were women according to them. The lowest share is found in the Arab Gulf States (4.8%) and the Asia region (12.9%). According to the Index, the percentage of the European Union, often vocal about gender parity, posts women to only 23.4 percent of its embassies, which is also quite low in comparison with the average – figures all far from parity.

Why does this matter? When women sit at negotiating tables, peace is more resilient. A UN Women meta-analysis of forty peace processes found that agreements involving women are 35 percent more likely to last at least fifteen years than those brokered by men alone. Women diplomats were pivotal to landmark human-rights compacts as well, from the 1979 Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women to the UN Security Council’s Women, Peace and Security agenda. They routinely link climate policy with social justice, broadening coalitions and directing aid toward the most vulnerable communities exposed to floods, droughts, and displacement which are often women and children. In the face of global challenges becoming more and more complex, the participation of women is more crucial than ever.

Yet barriers exist. A 2023 study of social media engagement showed that there is a discrepancy in online visibility between male and female diplomats with retweets on Twitter/X of women’s tweets 66.4 per cent lower than those of men. Inside ministries, women who reach ambassadorial rank are still disproportionately steered toward “soft” portfolios — development, culture, gender — rather than G-20 capitals, conflict zones, or energy hubs. The same glass walls appear in the UN system, where women make up a majority in agencies such as UNICEF but barely a quarter of professional staff in technical bodies like the World Meteorological Organization or the International Atomic Energy Agency.

Still, in the public imagination, the image of a diplomat is often that of a man. The old buddy network, the ambassadors’ parties where the wives are in a separate room: that image remains.

Structural hurdles compound these biases. Rotational postings uproot families every few years; many services still lack robust partner-employment support, affordable childcare, or flexible tele-working rules. Add the unspoken expectation that diplomats be “always on” and the caregiving, women are still mostly responsible for, and mid-career burnout becomes a matter of time.

The future of female changemakers

According to the UN, at the current rate it will take nearly a century and a half to achieve gender equality in the highest positions of power. But in the light of today's global crises we cannot afford to wait: We need action. Symbolic gestures, such as the UN’s designation of June 24th as the International Day of Women in Diplomacy in 2022, are important steps. But in 2025, what we need is not more commemoration, concrete action is needed.

It is long past time to provide women in diplomacy with the structural support required to meet the unique challenges of the profession. This means moving beyond token inclusion to real institutional change. For this, embassies need to offer partner employment support, dual-track postings, and childcare stipends and normalize remote and hybrid work for desk-based roles.

But logistical support is only one part of the equation. Women also need tailored preparation for the specific challenges they face, particularly in the digital age. Mentorship for junior women officers with senior foreign service officers could be crucial. Additionally, diplomats need to be equipped with tools to better counter modern-day challenges for diplomats like countering online harassment and boosting algorithmic visibility and elevating women’s voices in official social-media channels.

None of this is charity. Conflicts are multiplying, climate shocks intensifying, and multilateralism is under strain. At such a juncture the world cannot afford to leave half its diplomatic talent on the sidelines. The record shows that where women help shape negotiations, agreements last longer, address broader constituencies and mobilize fresh political will. Accelerating their full, equal and meaningful participation is therefore not a matter of symbolism but of strategic necessity – for peace, for prosperity and for the planet.