UK-EU summit

Geostrategy Matters!

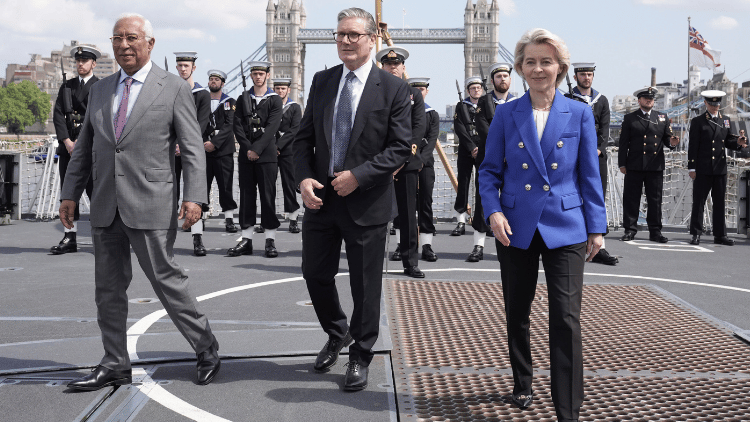

European Council President Antonio Costa, from left, Britain's Prime Minister Keir Starmer and President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen with members of the Royal Navy on board Type 23 frigate HMS Sutherland in central London, following the UK-EU Summit.

© picture alliance / ASSOCIATED PRESS | Stefan RousseauWell, it’s only a first step - yet a significant one: at their first summit meeting in the five years since Brexit, the United Kingdom and the European Union agreed on closer cooperation in several areas. The move was immediately met with loud criticism from the political right on the British Isles—from Eurosceptic Tories to Nigel Farage’s Reform UK party, which just performed remarkably well in the local elections, campaigning on familiar themes like the supposed “invasion” of “Little England” by migrants from outside the island. And skepticism isn’t limited to the UK. In Europe, especially in France, there are still voices that reject any idea of the British cherry-picking benefits—particularly when it comes to protecting national interests, mainly focused on agriculture.

Such voices should be ignored. The geostrategic imperatives that align British and European interests are simply too important. Since Putin’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 and Trump’s 2025 pivot toward Russia, NATO has been confronted with entirely new challenges. Putin’s Russia poses a threat to the European security, and Trump’s America can no longer be counted on as a reliable defender of freedom—surely not for the foreseeable future, perhaps not ever again. As a result, every European country must drastically increase its defense spending to more than three percent of GDP, which is likely to become the norm rather than the exception.

But even that won’t be enough. What’s also needed is a more integrated European defense market—one that includes British manufacturers, who are global leaders in certain areas of military technology. On the continent, each country has different strengths and priorities. A pan-European division of labor in the defense sector holds enormous potential for efficiency gains—gains already realized in less sensitive industries.

That’s why British Prime Minister Keir Starmer is not only politically astute but substantively correct to emphasize the potential of closer cooperation—through agreements on cybersecurity, for instance, and on the protection of maritime trade and undersea cables. Much more must follow, especially in the realm of defense markets, but also in other fields like scientific collaboration and the mobility of students and skilled workers—areas that have suffered greatly under Brexit. The UK remains, after all, a nation rooted in European values of freedom—more so than some EU member states. Just think of Viktor Orbán’s Hungary.

In fact, this post-Brexit rapprochement between the United Kingdom and the European Union could become a model for “variable geometry” partnerships. Increasingly, nations that share liberal democratic values might form “coalitions of the willing”—pragmatic alliances built not on existing treaties or political structures, but on shared purpose and readiness to act. And these alliances could extend well beyond Europe—to the global stage.