LIBERALISM

The Case for Liberal Pragmatism

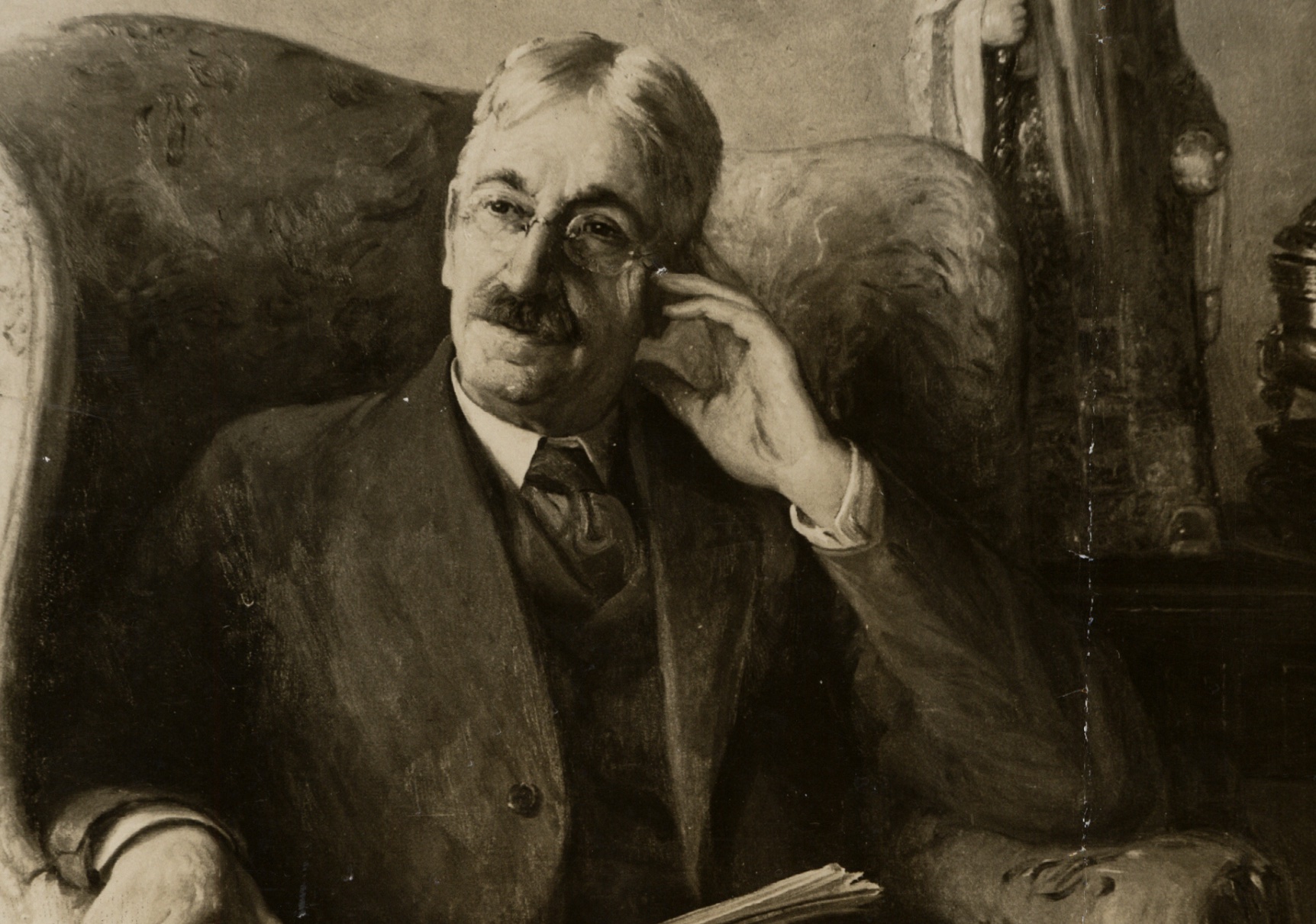

Photo of John Dewey.

© https://www.radicalteatowel.com/radical-history-blog/mr-democracy-the-life-and-work-of-john-dewey/The Philippines stands at a crucial crossroads. History will soon reveal whether the political turmoil triggered by the recent corruption scandal will give birth to a new kind of politics, or merely result in more of the same—new faces advancing the same rent-seeking, inward-looking, and protectionist policies that benefit entrenched local elites.

For decades, liberal actors in the Philippines have struggled to build a political project that truly resonates with the public. Their failures are not rooted in the weakness of liberal ideas, but in the way these ideas are practiced. Philippine liberalism has too often taken the form of moral idealism—principles-first, identity-bound, and insulated from the fears and aspirations of ordinary citizens. As a result, liberalism remains a lean movement, marked only by occasional moments of victory that analysts and campaign strategists feel compelled to explain with increasingly complex theories. The recent electoral successes of Bam Aquino and Kiko Pangilinan, for example, have been interpreted in multiple ways: the mobilization of the youth vote, discontent with the Marcos administration, the last-minute endorsement from the Iglesia ni Cristo (INC), or the effectiveness of their single-issue campaigns focused on education and agriculture. The point is this: whenever liberals win, the victory is almost always met with perplexity.

There is a fundamental flaw in how liberal elites, organizers, and academics understand the heuristics of political thinking in the Philippines. First, by “liberals” in this context, I do not mean the Liberal Party (LP). Rather, I refer to the loosely defined political movement that carries the torch of liberal ideas (freedom of speech, the supremacy of reason, and the essential role of markets) composed of social democrats, classical liberals, and modern liberals alike, often taking the name of “progressives”. For so long, this broader liberal movement has exhibited an inverse relationship between building ideological coherence and launching a popular campaign.

What has emerged instead is an ideologically incoherent movement that relies on a personality-based campaign strategy. This means that throughout the various attempts of “liberals” to merge into a united front, they have failed to form a coherent vision of economic prosperity and political progress around which a voter base can rally. Has anyone wondered in 2019 what Otso Diretso’s Florin Hilbay and Chel Diokno shared in terms of economic reform proposals, when the former clearly believes in small but efficient government while the latter favors greater statism and social redistribution? All the while, their supporters continue to wage personality-based campaigns rooted in moral purity, good governance, and the embrace of liberal pathologies. A recent field experiment by the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL) found that these one-way campaigns centered on personal identity and moral signaling performed significantly worse at persuading voters compared to deliberative and issue-based engagement. But how can the broad liberal movement compose a deliberative and issue-based platform when they have an incoherent party slate?

But this incoherence is not new.

In the Philippines in particular, the victory of liberalism in toppling the Marcos dictatorship and establishing the 1987 Constitution has produced a clique of political and intellectual elites who defend the Constitution against any potential revision, perhaps out of fear of repeating the circumstances that led to its creation. In doing so, the Constitution—with its economic and political provisions a mish mash of liberal and illiberal clauses, has upheld a version of Philippine development based on asset distribution as a way of social equity and protectionism as a way of nationalism.

Of course, liberalism does not claim infallibility. What it has is an openness to correct what does not work and do reform. But in the case of these liberals, they have effectively denied their capacity to commit failure by halting attempts to change the Constitution. In doing so, they themselves have effectively frozen the EDSA Legacy, rendering it incapable of accommodating new global conditions.

What we forget is that liberalism’s history is filled with adaptation, even borrowing from its ideological rivals. Liberalism is, by definition, one of the most flexible and adaptive political philosophies, its strength lies in its capacity for continual self-revision. This reflects the American philosopher John Dewey’s understanding of liberalism not as a fixed creed but as an evolving ethical and political practice or a “moving frontier”. For Dewey, liberalism succeeds when it remains experimental: when societies treat democratic life as a process of ongoing inquiry, continuously adjusting institutions, norms, and policies to meet new social challenges. Liberalism endures and prospers precisely because it is open-ended, committed to reconstructing itself rather than defending any frozen historical moment.

Dewey reminds us that liberalism was originally a political project that forged alliances under a common banner, against the infallibility of monarchies, the terrible abuses of autocratic regimes, and the entrenched inequalities of feudal societies. Adam Smith, in The Wealth of Nations, used emerging market principles to argue against feudal privileges such as royal monopolies, guild restrictions, and hereditary rents. Liberal political theorists also adopted republican traditions and social-contract theory—consent of the governed, separation of powers, and constitutional limits—which were adopted to place safeguards against absolutist forms of power. By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, liberals recognized that formal (or negative) freedoms were insufficient in the face of the inequalities produced by industrialism. Liberal economists such as Leonard Hobhouse and T.H. Green argued that the state must secure education, health, and social insurance to ensure greater liberty, a synthesis that formed the intellectual foundations of the modern welfare state.

Liberalism becomes an elite enclave of purists and highbrows only when it is transformed into an academic specialty rather than upheld as practical politics, as intended by thinkers like Montesquieu, Smith, and Kant, most of whom were themselves directly involved in political affairs.

Some have argued that liberalism in the Philippines has receded (or has died) as a political movement under Duterte’s presidency and the relentless feud between the Marcos and Duterte families. I echo the reflection of Daniel Cole and Aurelian Craiutu that these forecasts are largely exaggerated. I propose instead that the current political conundrum presents an opportunity for Filipino liberals to once again serve as the “moving frontier” by building a political party that is ideologically coherent and fostering a popular social movement that rallies around this ideology.

Whether this involves revisiting the Constitution to implement economic reforms that unleash the innovative capacity of the Philippines and pivot it away from protectionism, rethinking the political assumptions of our “sector-based” party system in favor of a stronger system grounded in political ideologies and performance-based accountability, or utilizing public campaign tools and alliances often considered taboo (such as mass influence operations), today is the ideal moment for liberals to be pragmatic and experimental.