Argentina

Is the Global Economy Changing?

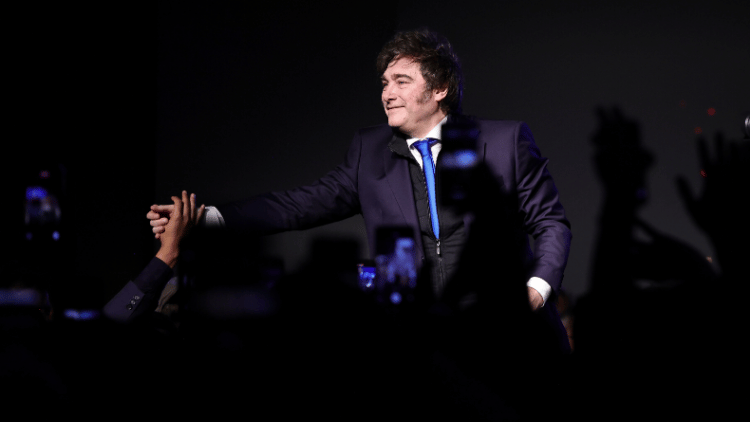

Under President Milei, Argentina is experiencing impressive economic growth and stability.

© picture alliance / ASSOCIATED PRESS | Nicolas AguileraIt is high time to rub our eyes and take a closer look at the global economic trends of the past year. The real structural break—contrary to the spirit of the times—is taking place in a nation that was previously known for good soccer, good beef, and good wine: Argentina.

It is a country that was one of the richest in the world in the 1920s, but since then has squandered all its (enormous) opportunities over many decades through an excessive state apparatus, high public debt, regular state bankruptcies, and high inflation, almost regardless of who was in government. The ideology of “Peronism” prevailed – a crude mixture of devout state socialism and corrupt state practices. Javier Milei, who has been president for a year and a half, has put a radical end to this.

His liberal economic and financial program of drastic cuts brought drastic reductions in government spending in virtually all areas and an opening up of the market economy. This worked, after a sharp, dramatic but relatively short recession, which also caused poverty in the country to rise temporarily, there has been a dynamic economic recovery in recent months, most recently with real growth rates of almost 6 percent. And this with an inflation rate that has fallen from over 210 percent (!) anually to below 40 percent—still too high, but already well on the way to rates that characterize stable countries, especially since the national budget shows a surplus of 0.4 percent of gross domestic product (GDP). The days when the finance minister could easily get the central bank chief to finance “his” deficit by printing money are clearly over.

The development of foreign trade is particularly sensational. In this regard, observers – including the author – were skeptical for a long time as to whether Javier Milei would maintain capital controls and the non-convertibility of the Argentine currency, the peso, for fear of accelerating inflation. But lo and behold, pressure from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to accelerate the opening of foreign trade helped Milei get back on his feet. The IMF simply made this a condition for further support loans, and the libertarian anarcho-capitalist Milei, who actually thinks little of the IMF, gave in – and rightly so, because it helped to restore the heavily devalued peso as a stable means of payment, even against the dollar. The market-driven devaluation of the peso was even less than feared, with the weakness of the dollar due to Trump's policies acting as a helping hand for Argentina.

The bottom line, a remarkable success story, especially since poverty in the country has recently declined and Argentinians and foreigners alike are gradually considering whether it might be worth investing in this country – with its market economy orientation and stable currency. In any case, Argentina's full return to the international capital markets is long overdue, and many Argentinians themselves are considering repatriating their savings, which have been parked abroad for decades.

What a transformation of the global economy! Argentina, once the problem child, could become a model student—and thus another example of success in South America, the economically troubled continent, alongside Chile and Uruguay, where, however, the political situation has been far less spectacular. Let's not kid ourselves, though, Milei still faces deep structural reforms that are necessary to restore the resource-rich country to the dynamism it had 100 years ago. But at least a courageous start has been made. One could proclaim dramatically, a great continent is awakening, at last.

What a contrast to the US and Europe. Donald Trump is leading his country into an inflationary spiral with waves of protectionism, high financial deficits of six to seven percent of GDP, and a devaluation of the dollar, making foreign products more expensive—an extremely dangerous mixture of mercantilist stubbornness and economic folly. Europe, on the other hand, is running up massive debts – apparently out of a misguided belief in the omnipotence of the state and the insignificance of the interests of future generations. France's budget deficit is almost 6 percent of GDP, Britain's is a good 4.5 percent, and the debt-to-GDP ratio in these countries has long since passed the 90 percent mark, as it has in the US. Germany is still lagging behind, but the Merz/Klingbeil government is doing everything it can to close the gap. All of this poses enormous risks to the stability of the capital markets – just as it did a good two decades ago in the run-up to the global financial crisis.

In short, the global North is living off its assets, which begs the question, how much longer can this continue? And the global South – Argentina, at least – is finally building up its assets. Objectively speaking, one can only respect this, even if Javier Milei hardly misses an opportunity to alienate global sympathizers for his convincing liberal economic and financial program with his overly sharp populist rhetoric. But for an objective judgment, one needs to look at the substance of the politics—and not just the crudeness of the rhetoric. And in that regard, Milei's record is not bad.