PHILIPPINES

Defending Freedom Across Generations: Liberalism in an Aging Philippines

Senior citizens from the Philippines.

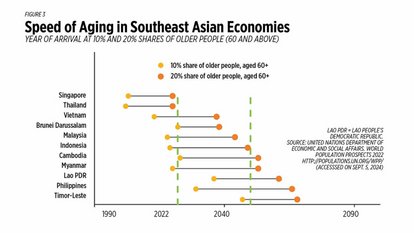

© Manila BulletinIn just five years, the Philippines will officially be an aging society. That should surprise—and worry us. After all, this is still a country where half the population is under 25. Yet in 2020, there were already 9.24 million senior citizens (60 years and above), or 8.5% of the population. By 2066, one in five Filipinos will be elderly.

This demographic shift is not just about gray hair and longer lives. It will shape the country’s politics, its economy, and its freedoms. As older Filipinos grow in number, their political clout is becoming impossible to ignore. In the 2025 elections, they already account for 16.8% of registered voters. Known for high turnout, older cohorts who prize stability, economic security, and tradition carry significant weight at the polls. This is not unique to the Philippines. Japan’s politics are dominated by pensioners, while in the United States, seniors consistently shape national debates on healthcare and social security.

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs

In a democracy where numbers matter, politicians will increasingly tailor platforms to win the “gray vote.” But without fiscal capacity, promises of bigger pensions and subsidies risk being financed by debt or heavier burdens on younger taxpayers. That is the seedbed of intergenerational resentment, when the young feel they are paying for a system that won’t be around when they grow old.

The Philippines enters this transition with weak foundations: the Social Security System may be depleted by 2054, while the GSIS is healthier but covers only a small slice of workers. Meanwhile, four in ten remain in the informal economy, excluded from pensions and health insurance. Working children, already battered by high food and healthcare costs, often serve as the safety net of last resort for aging parents. A single hospitalization can exceed the average annual income of ₱227,000. The result is the so-called “sandwich generation”: working adults supporting both their children and their parents, often at the expense of their own future savings. For many Filipinos, dignified aging is a privilege, not a guarantee.

So far, the State’s response has been short-sighted and populist. Politicians dole out monthly ayudas or promise across-the-board pension hikes. Others even propose coercive laws. The “Parents Welfare Bill,” which criminalizes children for failing to support parents, only exposes the State’s inadequacy: ruling by guilt instead of building an effective system.

Populism may promise quick relief, but it cannot give security or sustain dignity. The real problem is structural: an economy too weak to generate the jobs, taxes, and savings needed to make aging secure.

Given these trends, liberals in the long haul should articulate a coherent vision of active aging. This means treating older Filipinos not as passive recipients of charity but as individuals with the freedom to remain productive, independent, and dignified for as long as they wish. In other words, empowerment—not dependency—is the goal.

That requires ensuring access to decent jobs, opportunities for lifelong learning, and participation in community and civic life. It also means bridging the digital divide. Today, only 18% of Filipinos aged 65 and above possess even one basic ICT skill, the lowest among all age groups. Yet essential services such as banking, telehealth, news, and disaster management are moving online. Unless addressed, digital exclusion will trap millions of older Filipinos in isolation while exposing them to scams and misinformation.

Filipino liberals should take sweeping steps to expand older Filipinos’ positive (“freedom to”) and negative (“freedom from”) freedoms.

First, freedom to prosper through openness. The foundation of social protection is a strong economy. Put simply, the country cannot subsidize aged care without resources. Liberalizing trade, removing constitutional restrictions, and attracting higher-quality investments will expand the tax base, provide jobs both to young and older workers, and finance future pensions and healthcare. Ultimately, a strong economy frees children from carrying the entire burden of their parents’ expenses.

Second, freedom from high costs. Supporting loved ones should not mean being crushed by high prices. Yet food inflation in the Philippines remains among the highest in ASEAN. Reforms in agriculture—deregulating inputs like fertilizer, consolidating farmland for efficiency, and liberalizing rice and corn importation—can lower food costs and reduce malnutrition. With more disposable income, families would be freer to support both children and aging parents without falling into debt.

Third, freedom from unsustainable and unfair safety nets. The Philippines loses hundreds of billions annually in tax leakages, from ghost receipts to fake senior discount IDs. A 2023 estimate pegged foregone VAT alone at over ₱500 billion annually. Smarter regulation and digital tax enforcement can plug these gaps, freeing resources for social protection.

Fourth, freedom from discrimination. Ageism in employment, healthcare, and politics undermines freedom as surely as poverty does. Liberals must champion the equal rights of all Filipinos—young or old—to work, vote, speak, and participate fully in public life. A step forward was the April 2025 push by the Philippines at the UN Human Rights Council for a treaty on the rights of older persons. But implementation will take sustained effort. Age-based job bans, healthcare neglect, and belittling stereotypes remain stubborn barriers.

Fifth, freedom to navigate the digital age. To deny digital access is to deny freedom. From online banking to healthcare, digital access is now essential for older Filipinos to thrive. Ensuring competitive telecoms, user-friendly devices, age-appropriate digital literacy campaigns, and protection against online fraud are crucial for meaningful aging.

Demographic change is not destiny. Without foresight, intergenerational solidarity may give way to resentment, leaving old and young alike vulnerable to populism. The Philippines is still young compared to its neighbors. But the “gray tsunami” is coming. For liberals, the present remains a window of opportunity.

The question is: are we thinking two, three steps ahead—or not at all?

Cesar Ilao III is Research and Communications Lead at the Foundation for Economic Freedom in Quezon City.