Serbia

"Did you say something?"

Student protests against the rule of Aleksandar Vučić in Serbia have been going on for over a year now. Cracks are beginning to appear in the previously flawless facade of Serbian autocracy. Social role models are abandoning the regime.

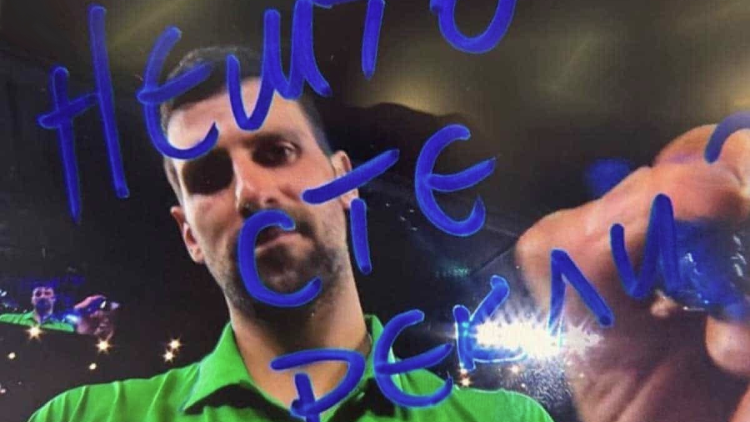

After his victory over Jannik Sinner in the semifinals of the Australian Open, Novak Djoković, Serbian tennis legend and constant savior of the Serbian soul for over a decade, wrote a cryptic message on the camera lens: "Нешто сте рекли?" ("Did you say something?"). And following his defeat in the final against Carlos Alcaraz, when the press conference was actually already over, he sent another message to the people in his home country: "I have a message for the people of Serbia: Justice and truth always prevail! Hang in there!" These were remarkable words from someone who had remained silent for many years.

Just minutes earlier, the host of the breakfast television show on the pro-government channel Pink TV had asked Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić who he was rooting for in the ongoing final, Alcaraz or Djoković? One could dismiss this as a superfluous, even trivial question. But in today's Serbia, where the omnipresent president's constant media coverage is taking on absurd proportions, everything seems to be scripted, so it doesn't seem unlikely that even this question is part of the staging.

Because, of course, the Serbian president always cheers on "our Novak", even when he is sitting in the television studio during the morning final match. And, of course, he regularly inquires about the score to show how interested he is and how he "believes in Novak's victory". But when this same Novak has been insulted and slandered for months by a tabloid newspaper that is also loyal to the regime, whose owner and editor-in-chief is also a good friend of the president, then it is at least questionable whether the president really always cheers for Novak – or whether he is not rather supporting the campaign of his good friend, who describes Djoković as a “failed tennis player.”

Since Djoković began supporting the students and their protests last season, the insults from members and vassals of the regime have not stopped. They exemplify how the Serbian government treats anyone who eludes its complete control – even if, as in Djoković's case, that person is a symbol of Serbian success, a "national brand" and an object of collective pride. Djoković was only acceptable to this government as long as he remained silent, as long as he won, and as long as his victories could be exploited for the daily dose of state propaganda – just as another Serbian sports icon, basketball player Nikola Jokić of the NBA team Denver Nuggets, does.

The judiciary is dying a quiet death

Seven-time Wimbledon champion Novak Djoković is a symbol of individual excellence who owes nothing to the system. On the contrary, he has achieved success despite this system. But an authoritarian regime does not tolerate autonomy. It demands loyalty, silence, and a willingness to serve as nationalistic window dressing in a carefully staged "Truman Show".

It is therefore no coincidence that the smear campaigns against Djoković and all those who have dared to raise their voices for months are accompanied by a systematic destruction of the rule of law. The most recent and perhaps most dangerous example of this is a so-called "judicial reform" initiated by the ruling SNS party.

This was passed without parliamentary debate and fundamentally shifts the balance of power between the executive and the judiciary. The independence of the public prosecutor's office is curtailed, its responsibilities and powers politicized, and the work of the public prosecutor's office for organized crime, which recently even indicted a minister, is practically paralyzed. President Aleksandar Vučić signed the law on January 30, and it came into force on the same day. Critics see this as nothing less than the end of the EU integration process.

Under the pretext of reform and efficiency, the government is undermining one of the last institutions that counteracted the arbitrariness of the executive branch. Instead of an independent public prosecutor's office, Serbia is getting one that has to bow to political demands. Instead of justice, Serbia is getting selectivity. And instead of the rule of law, Serbia is getting the will of a power centre that stands above democratic institutions.

Civil or gratuitous courage?

In this system, Novak Djoković's message to his compatriots that "justice and truth always prevail" is not an empty phrase, but a subversive statement. It reminds us that institutions exist to protect citizens, not the government. That laws are not subject to political agreements. That the public prosecutor's office is not an instrument of the executive branch. And that the protesting students are not enemies of the state, but want to set things right.

That is why the question written on the camera – "Did you say something?" – resonates far beyond the tennis court. It is directed at the regime, which pretends not to hear the population. But it is also directed at the media, which denies and distorts reality, as well as at other democratic institutions that remain silent or have been silenced.

Ultimately, the question is directed at everyone who believes that authoritarianism can be normalized if it is packaged with enough patriotism and the people are numbed by constant propaganda. Whether you approve of it or not, Novak Djoković's question has become a litmus test for Serbian society.

Novak Djoković's great and important advantage over the rest of Serbia is his autonomy. It allows him to decide for himself where he wants to continue his life with his family. For the majority of Serbs living in Serbia today, this is hardly imaginable.

Edita Barać-Savić is a project manager for civil society cooperation at the Western Balkans office of the Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom in Belgrade.