Thailand

Thailand: Hope for change, longing for stability

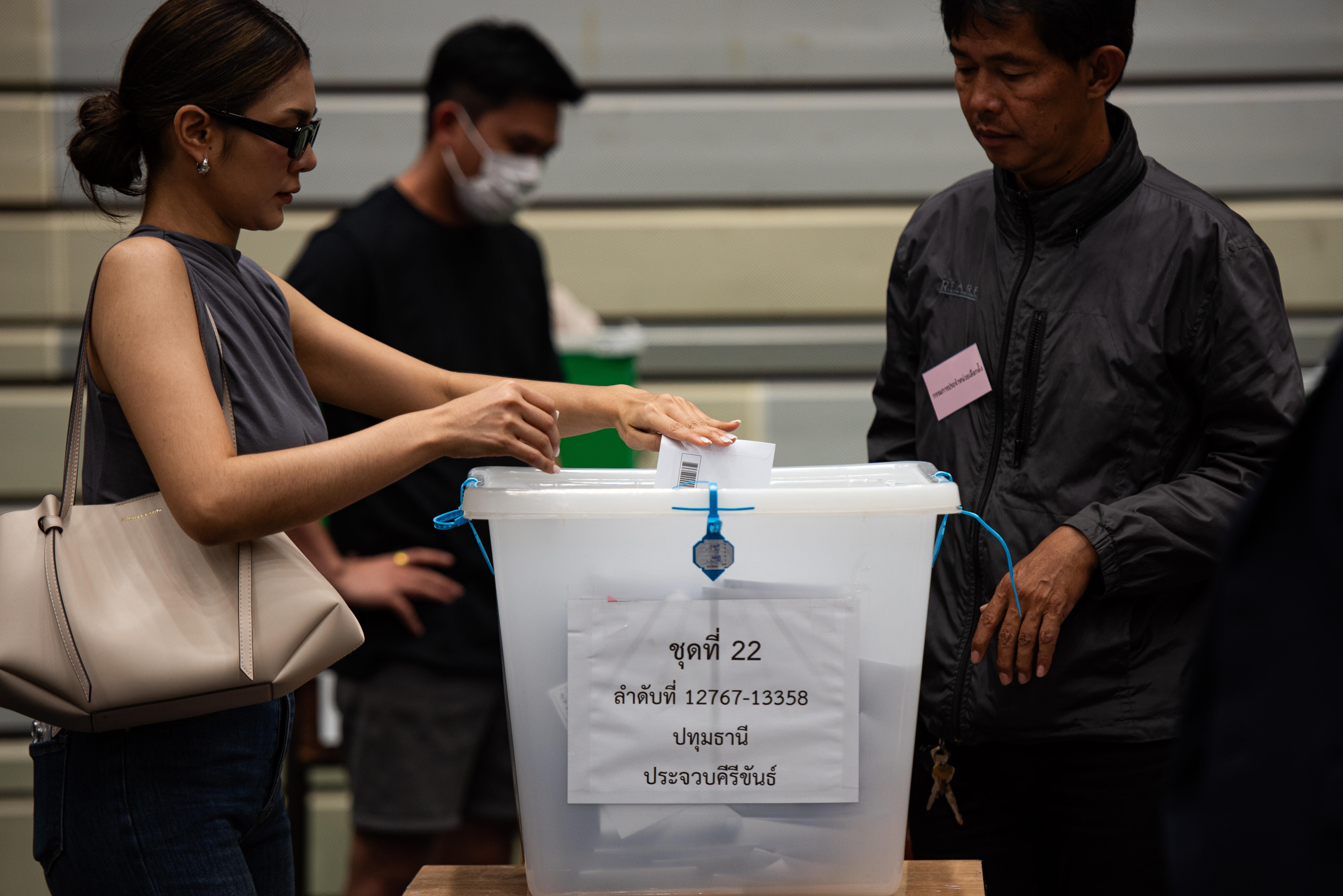

Wähler geben ihre Stimmen in einem Wahllokal im Thai-Japanese Stadium Building im Bezirk Din Daeng während der vorgezogenen Stimmabgabe in Bangkok, Thailand, am 1. Februar 2026 ab.

© picture alliance / Sipa USA | Teera NoisakranOn 8 February, the Thai people will elect a new parliament. They last cast their votes less than three years ago. The intervening period has been turbulent. Two heads of government have been removed from office, the largest opposition party has been banned, and there has been an escalation on the border with Cambodia. Many Thais now long above all for stability. They hope that this will finally lead to more economic growth.

Shortly before the election, polls show that only 14 per cent of voters are still undecided. Unlike in 2023, when the political landscape in Thailand was highly polarised, voters are now making their decisions based on content rather than emotional aspects, says Pornpan Buathong, head of the Suan Dusit poll, in an interview with ThaiPBS. ‘People today are less concerned with “left” or “right” and more focused on the state of the country – especially the economic situation,’ she says.

So far, the progressive People's Party is ahead in the polls. It is campaigning on a platform of combining institutional reforms with economic renewal. Unlike three years ago, this time it is placing greater emphasis on concrete economic policy measures. A 100-day programme worth around THB 250 billion (approximately 6.7 billion Euro) is intended to stimulate growth, boost investment and provide liquidity to small and medium-sized enterprises after an election victory. With this expensive election promise, the party aims to achieve its declared goal: to obtain an absolute majority so that it does not have to rely on forming a coalition. In 2023, the party's focus was even more strongly on proposals to amend the lèse-majesté law and limit the political influence of the military.

The former ruling party, Pheu Thai, weakened by the removal of two heads of government and the imprisonment of its powerful ex-Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra, is focusing on continuity and social security. It wants to free the Southeast Asian country from the ‘middle income trap’ and relieve workers, especially those in the informal sector, of excessive debt. This is a serious problem: private debt among Thai households has now reached more than 90% of gross domestic product. The populist election promise of the Pheu Thai party to give away one million baht (just under 27,000 Euro) to nine people every day in order to generate ‘nine millionaires in one day’ has caused quite a stir: critics believe that the money should be used for educational measures or other sustainable purposes.

The Bhumjaithai Party (BJT) could play a key role. It is currently in power, and its leader, Anutin Charnvirakul, is Prime Minister. He dissolved parliament prematurely in December to pre-empt a foreseeable vote of confidence. The conservative and pro-monarchy BJT positions itself less on the basis of a comprehensive reform narrative than on security policy issues. In particular, the recent escalation of the border conflict with Cambodia has raised its profile. National security, territorial integrity and the state's ability to act have thus come to the fore.

The Democrat Party is striving for a political comeback. Under the renewed leadership of former Prime Minister Abhisit Vejjajiva, it is positioning itself as an economically liberal and institutionally reliable force that opposes shady money flows and corruption. It continues to enjoy stable support in the south of the country. Nevertheless, it lags significantly behind the leading parties in the polls. A role as a coalition partner is conceivable.

Economic issues take center stage

Three years ago, hopes for political change were still high. The charismatic Pita Limjaroenrat led the progressive Move Forward Party (MFP) to electoral victory. But he did not come to power. His party was banned by court order and Pita was excluded from politics for ten years. The MFP was re-founded under a new name and is now called the People's Party. Pita is only allowed to participate in election campaign appearances in a supporting role. His successor as party leader, Natthaphong Ruengpanyawut, has not been able to match Pita's popularity.

However, the People's Party now has a slightly easier time than it did in 2023. At that time, senators appointed by the military were involved in the election of the prime minister. However, the relevant transitional provision in the constitution has since expired. Now the lower house alone elects the head of government.

However, the removal of the Senate clause alone does not guarantee a political breakthrough. The interference of supposedly independent institutions in the political process in recent years has been too deep. The Constitutional Court, the Election Commission and the National Anti-Corruption Commission have repeatedly destabilised governments, dissolved parties or disqualified leading politicians.

Political instability hinders growth

The economic situation lends additional weight to political issues. According to the World Bank, Thailand's economic growth last year was around 1.8 per cent – significantly lower than that of other ASEAN countries. Vietnam's growth was more than three times higher. Although Thailand is a key production location in Southeast Asia, political instability has dampened the confidence of many investors. Economists and business associations warn that ongoing uncertainty is slowing growth and further increasing pressure for reform.

The key question remains whether the progressive People's Party, should it win the election again, could actually come to power and reform the country. It is also possible that the party will once again be thwarted by political manoeuvring and the judiciary. Many voters are going to the polls with muted expectations. In Thailand, even a clear victory at the ballot box does not guarantee a secure takeover of power.

Vanessa Steinmetz heads the FNF's Thailand office.