Syria

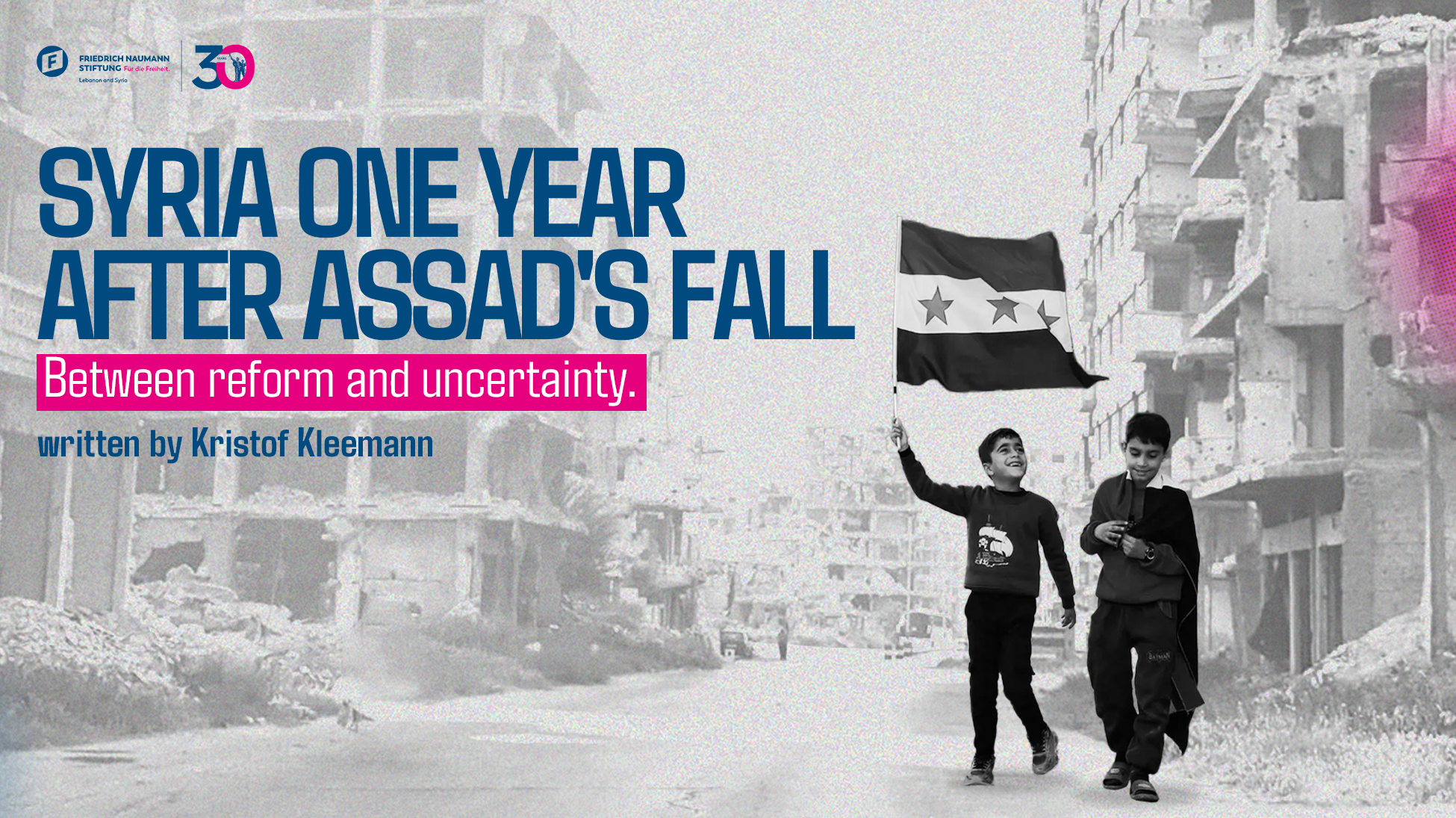

Syria one year after Assad's fall

One year after the collapse of the Assad regime, Syria finds itself in a moment that is both historic and unsettled. The end of decades of authoritarian rule raised expectations of political renewal and economic recovery, yet the transition has unfolded in a landscape shaped by war damage, fragmented authority structures, and widespread distrust. The new leadership inherited a state whose institutions, infrastructure and social fabric had been weakened to the point that even basic governance became a challenge. Against this backdrop, the first twelve months reveal a mixed picture: early signs of reform, but also the overwhelming reality of a state emerging from institutional collapse. The government has tried to set a direction for renewal, beginning with steps that rebuild administrative capacity and signal a break from the past.

Reform measures and government progress

The new government appointed experts with international experience in finance, infrastructure and technology to key ministries. At the same time, reconstruction of administrative structures began, for example at the central bank, which underwent a major reorganisation.

There has been initial economic progress: the country has returned to the SWIFT payment system. Additionally, investment projects totalling four to five billion US dollars have been announced, primarily in the energy and telecommunications sectors. However, these projects remain declarations of intent for the time being. Investors are hesitant due to sanctions and an uncertain legal framework.

Nevertheless, there have been some improvements in everyday life. In 2025, electricity production reached around 2,400 megawatts nationwide, which is progress, but not enough. While Aleppo and Damascus received up to 20 hours of electricity per day at times, rural areas continue to experience significantly worse supply. The World Bank forecasts growth of around one per cent for 2025, which is symbolic but indicates initial stabilisation.

Internal conflicts and structural hurdles

The transition is taking place in challenging circumstances. Large parts of the country are beyond the control of the central government. Local power centres that emerged during the war continue to influence politics and the economy. This fragmentation hinders the establishment of state authority and uniform administrative action, and slows down reforms.

In Daraa, in the south-west and along important transit corridors, clan structures and former rebels dominate. Kidnappings, attacks and violence are commonplace. In Suweida, home to the Druze minority, scepticism towards the new government continues to prevail. Escalations of violence have created deep divisions, leaving many residents doubting the government's ability to ensure security.

On the coast, rivalries within Alawite networks are exacerbating the situation. In the northeast, the Kurdish-dominated Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) control key oil and gas fields, as well as administrative structures. A deal between the government and the SDF is crucial for securing territorial unity and energy sovereignty. However, alongside the internal power struggle in Syria, Turkey opposes any strengthening of the SDF, viewing even limited autonomy efforts as a threat.

Security policy and the international dimension

Progress has been made in security policy despite the challenges. According to the government, nationwide operations have resulted in the arrest of individuals suspected of being extremists. The organisation ACLED has recorded a decline in attacks in urban areas.

A turning point came with President al-Sharaa's visit to Washington. The US has intensified its cooperation with the new government, providing joint reconnaissance, technical support, and coordinating operations against ISIS cells, for example. Washington views a more stable Syria as an opportunity to mitigate cross-border threats and thereby ensure Israel's stability.

Social cohesion and economic liberalisation

In addition to security policy issues, social restructuring and economic liberalisation remain key tasks. President al-Sharaa's legitimacy is based on a transitional constitution and an election whose competitive conditions were severely restricted, making it more akin to a selection process. The vote marked the symbolic beginning of the transition rather than a genuine democratic process. In the coming years, it will be crucial to establish stable institutional foundations for political participation. This includes establishing a binding timetable for the constitutional process, ensuring independent election monitoring, and implementing reforms to media and party law that enable public debate and organisational diversity.

The constitutional process itself is still in its infancy. It must clarify how the executive and legislative branches will be legitimised in future, which separation-of-powers mechanisms will be effective, and how minority rights can be guaranteed by the constitution. Another key area concerns transitional justice and property rights. For many people wishing to return, dealing with past expropriations remains a crucial issue, as does the question of economic prospects. Without transparent procedures for clarifying ownership, restitution or compensation, reintegration is unlikely to succeed. At the same time, questions about amnesties, reintegration programmes, and security service reforms remain unresolved. These are intended to both protect returnees and curb informal power structures. Instruments such as DDR and SSR programmes, ombudsman offices and local security pacts could provide reliable protection for minorities and vulnerable groups. However, transitional justice must not be limited to dealing with the past. It must also establish mechanisms to prevent future abuses and thus strengthen trust in the new state.

So far, minorities such as Alawites, Christians, Druze and Kurds have reacted with mixed feelings. The loss of the old order raises questions about protection, participation and cultural self-determination. The first civil society initiatives are emerging in cities, often supported by returnees or exile networks, and these initiatives promote education, career prospects and local reforms. But deep mistrust remains. Many Syrians fear that political participation could once again be tied to loyalty and personal networks rather than constitutional procedures. This is precisely why economic reforms are so important. In transitional societies, institutional trust is built more through visible improvements in everyday life than through political announcements. Market liberalisation can play a key role in this process. Where companies invest, jobs are created and prices remain stable, there is a growing belief that the reforms are having a positive impact on society as a whole, and not just benefiting certain groups. Such reforms also convey a sense of optimism.

Against this backdrop, the new government's approach is notable. The decision to push ahead with economic liberalisation marks a clear break with the state-centred economic order of recent decades. The fact that a significant proportion of the new parliament supports this approach lends additional political credibility to the reform agenda. A more open economic order creates incentives for investment and opens up access to economic participation for new social groups. However, its potential remains limited while structural obstacles remain in place, such as blocked financial channels, unclear legal frameworks, and sanctions that continue to cause the international financial sector to exercise great caution.

While the waivers and the US government's decision to lift the Caesar sanctions send an important signal, they do little to improve economic conditions. Banks are guided not by political announcements, but by long-term legal certainty. Financial institutions will remain cautious as long as it remains unclear whether the sanctions will be lifted.

This situation is slowing down economic liberalisation. Even where reforms are taking effect and investors are showing interest, blocked payment channels and fears of new sanctions are preventing the signing of long-term contracts. International de-risking remains the biggest stumbling block, with the impact of reforms being limited.

Outlook: Opportunities under pressure

One year on from the political change, it is clear that Syria has the chance for a new beginning, with reforms, diplomatic openness and progress in security policy all showing promise. However, the process remains fragile. The success of sustainable institutional reconstruction depends on simultaneous advances in security, the rule of law, and economic openness, as well as on an international sanctions policy that enables reforms.

The country is at a critical juncture where progress could easily be reversed. Without solutions to issues of institutional credibility, investment protection and territorial order, Syria risks remaining in a state of limited stability.

Germany could support this process by providing technical expertise in areas such as building state institutions, reforming financial administration and creating reliable investment conditions. A coordinated European stance on sanctions is equally important. Partial relaxations or waivers are not enough — a stable political framework that recognises progress while addressing security concerns is needed.

Syria is undergoing change. The success of the new beginning depends on the convergence of political will, reforms and international support. Only then can the current opening lead to a sustainable future