Social Mobility

Trapped in the Social Loop: The Challenges of Social Mobility in Morocco

Where dreams are often separated by the apparent unreachability of the ladder of opportunities. Social imbalances cast a shadow from kindergarten to the workplace, keeping a significant portion of the population trapped in what seems like an unbreakable cycle. These inequalities run deep and hinder development from the earliest stages of life. This article seeks to shed light on the complex mix of social disparities, exclusions, and systemic obstacles that block the path to progress.

Navigating Social Hurdles: Morocco's Battle Against Inequality and Marginalization

The concept of social mobility, which represents the connection between an individual's occupation or income and that of their parents, reveals an unsettling truth. In Morocco, this link remains remarkably strong, limiting the opportunities for social advancement and perpetuating a sense of inequality.

According to the enlightening Global Social Mobility Index compiled by the World Economic Forum in 2020, Morocco finds itself mired in a disheartening 73rd position out of 82 countries. This ranking reflects critical factors such as health, education, technology, work, and institutions. Morocco trails behind neighbouring countries like Tunisia, ranking 62nd, and Egypt, at 72nd. In stark contrast, countries like Denmark, Norway, and Finland comfortably secure the leading spots.. These rankings offer a wake-up call, casting a stark spotlight on the formidable challenges of social mobility within the Moroccan context.

The outcomes of this study merely confirm what I discovered during my interviews with various individuals from different socioeconomic backgrounds, including passionate young students, and seasoned politicians. It seems to be an indisputable social truth that individuals hailing from disadvantaged families face formidable structural barriers within Moroccan society. Access to quality education in Morocco, predominantly through private institutions, is a privilege primarily reserved for the upper middle and upper classes.

The words of Houssam Boutadghart, a determined law student who navigated the public school system, resonated deeply: "If you come from a humble family and dream of success, you practically need to possess extraordinary brilliance to overcome the hurdles of Morocco's inadequate education system". This reality is also evident to some parents from the lower middle class. Understanding that education is the key to success, they choose to make significant financial sacrifices and send their children to expensive private schools to provide them with better opportunities.

Regrettably, this disparity in educational opportunities parallels the limited access to decent, well-paying jobs, further exacerbating the social divide.

Moreover, territorial disparities intensify the problem, with marginalised rural regions in Morocco, where poverty is particularly prevalent, being particularly affected. Considering that around 36 percent of the total population in Morocco living in rural areas (World Bank, 2021), a perpetuating cycle of social dynamics hinders any hope for upward mobility.

Early Steps, Lasting Impact: Pre-school Education and Social Mobility

Disparities in educational opportunities in Morocco begin early, even before primary school. Experts and numerous studies agree that preschool education is important for developing cognitive and socio-emotional skills that contribute to future success. However, access to quality preschool education in Morocco is heavily influenced by factors such as place of residence (urban or rural) and the family's socioeconomic background.

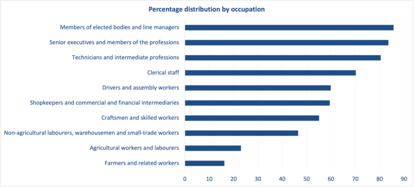

The new study by the Moroccan independent government statistical institution (HCP) highlights that children whose fathers have a higher education degree are nearly three times more likely to access preschools compared to children whose fathers have no education or only primary education. Moreover, only 16% of children from farming families attend preschools, while the number exceeds 85% for families with high-ranking profiles in managerial positions (See Figure).

Figure: Percentage Distribution of Children in Preschools by Fathers' Education and Occupational Groups (Source: HCP)

Even though since 2018 Morocco has been implementing a large program to broaden access to quality preschool education, it remains a luxury for many disadvantaged Moroccan children. According to Ismail El Hamraoui, regional director at the Ministry of Youth, Culture, and Communication, the solutions lie in making preschool mandatory for children from the age of 4, constructing preschools near existing schools, and encouraging companies to offer preschool services to their employees.

Enhancing access to quality preschool education through increased investment is a powerful tool to increase social mobility (Barnett & Belfield, 2006). By extending these early opportunities to all Moroccan children, regardless of their backgrounds, the country can begin to balance inequalities and build a firm foundation for future educational success. This approach not only empowers children to tap into their full potential but also contributes to disrupting cycles of intergenerational hardships. Despite the multitude of factors in a child's life, a quality preschool education can make a substantial difference and set the stage for a better future not just for individuals but also for society.

Unlocking Morocco's Future: A Call for Educational Equality

"…There's only one way out: 'You must excel in your studies. There's no other option. No different path.'" Rania Elghazouli recalls her mother's emphatic words, words that underscored her family's unyielding commitment to education. Such firm conviction and substantial investment in private schooling steered Rania's life journey. Today, she passionately upholds this family tradition, making her children's education a top priority.

Regrettably, the opportunity to attain the private education that significantly shaped Rania's life remains elusive for most in Morocco. Only 14% of over seven million students have access to it (Morocco World News, 2019). This educational discrepancy is exacerbated by the instability of the public education system, influenced by political uncertainties and frequent changes in policy. Parents who ardently seek high-quality education for their children are left with no other choice but the foreign private school systems, such as the demanding private French schools known for their rigorous entrance examinations.

A study by the Conseil Supérieur de l’Éducation, de la Formation et de la Recherche Scientifique (CSEFRS, 2019) shows that students in private schools outperform their counterparts in public schools, with an average score of 461 compared to the standard performance of 340 for public school students in the past academic year. The discrepancy is largely attributed to superior resources, proficient teachers, and conducive learning environments in private schools, while public schools grapple with restricted funding, deficient infrastructure, and subpar teaching quality.

The situation is made more critical by the alarmingly low literacy rates among Moroccan children. The World Bank’s “Learning Poverty Report 2022” highlights that an average of 64.9% of children under the age of 10 are unable to read a simple text. These formidable obstacles underscore the urgent need for comprehensive reforms and policy interventions that bridge the gap between private and public schools and address the systemic issues hindering social mobility in Morocco.

This reality sheds light on a deep-rooted educational inequality in Morocco, where a weak education system poses a challenge to the country's socio-economic stability, sustainable development, and overall well-being. The system perpetuates opportunity gaps, obstructs social mobility, and widens the gap between the privileged few and the majority. This dynamic inadvertently reinforces the dependence of political and economic elites on the existing power structures , presenting a complex challenge to democracy and political participation. The limited access to quality education and opportunities for advancement curtails the ability of marginalized groups to break free from the cycle of inequality while consolidating the power and influence of the ruling class.

Uphill Battle: Moroccan Universities Struggle to Empower Students and Bridge the Opportunity Gap

In the Moroccan educational landscape, stark realities at the high school level hint at systemic issues. A formidable hurdle to higher education and subsequent social mobility presents itself in the form of the Baccalaureate exam. A substantial number of young Moroccans fail to clear this critical gateway to further education. Among the fraction that does succeed, only a slim portion—50,000 out of 200,000— will receive training that aligns with their employment expectations, leaving approximately 140,000 individuals acquiring skills that hold little value in the labor market. Disappointingly, a mere 10,000 young people, accounting for less than 2 percent of the age group, will attain highly skilled degrees, which assure appealing career opportunities and earning potential (Chauffour, World Bank Group, 2018).

The challenges persist and even amplify as students progress to the university level. Evidenced by a success rate of a mere 13.3%, most students in Moroccan universities struggle to obtain their bachelor's degree within the expected three-year timeframe. An alarming number require six or more years to graduate, resulting in an average duration for a bachelor's degree of four and a half years (Lematine.ma, 2018).

However, it's not merely a case of delayed graduations. The quality of education at the university level often fails to meet the demands of the job market, creating a chasm between academic training and employment prospects. The scarcity of resources, inadequate teaching quality, and a curriculum that doesn't reflect the skills sought after in the labor market all contribute to this disconnect.

The radical divergence between the education system and labor market requirements was aptly encapsulated by Abdeselam Seddiki, the former Minister for Employment and Social Affairs, who stated, "The social elevator goes up empty and comes down full".

This mismatch has far-reaching consequences. The widening gap fosters frustration and despair among young individuals who struggle to secure employment opportunities that are compatible with their academic qualifications and career expectations. It raises significant barriers to their social mobility, reinforcing a cycle of stagnation and disenchantment.

To rectify these issues, a fundamental restructuring of the Moroccan education system is called for. Priorities should be realigning teaching quality and resources with market demands, bridging the gap between academic learning and job market competencies, and fostering an environment that truly promotes social mobility Moreover, it is crucial for the ministries responsible for education and employment to intensify their communication and collaboration, ensuring a coordinated approach to tackle these issues effectively. By taking these steps, Morocco can unlock the full potential of its young population and cultivate a more prosperous and equitable future.

Conclusion

The analysis of interviews, studies, and articles suggests that it would be beneficial to give greater attention to the issue of social mobility in Morocco. A deeper investment in early childhood education and a focus on bridging educational inequalities could help Morocco harness its potential more effectively. Collaboration, possibly with support from countries like EU member states with higher social mobility indices, could make a positive contribution to developing a more equitable society, where improved social upward mobility in Morocco becomes more achievable. Ultimately, this endeavour could pave the way for a Morocco where dreams for the underprivileged are not seen merely as distant possibilities but can be transformed into tangible reality.

The author is a student of economic engineering and an intern at FNF Morocco